Gerald Horne will lead a webinar on the life of William L. Patterson on Monday April 24th at 8:00 PM. Click here to register.

Gerald Horne, Black Revolutionary: William Patterson and the Globalization of the African American Freedom Struggle, University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Walter Howard, We Shall Be Free: Black Communist Protests in Seven Voices, Temple University Press, 2013.

The Party’s contribution to the struggle for racial equality in the US is part of the historical record, although it rarely gets the attention it deserves in historical accounts. Two recent books go far toward filling this void and providing a much needed window on this topic by zeroing in on the life of one towering figure in this riveting story.

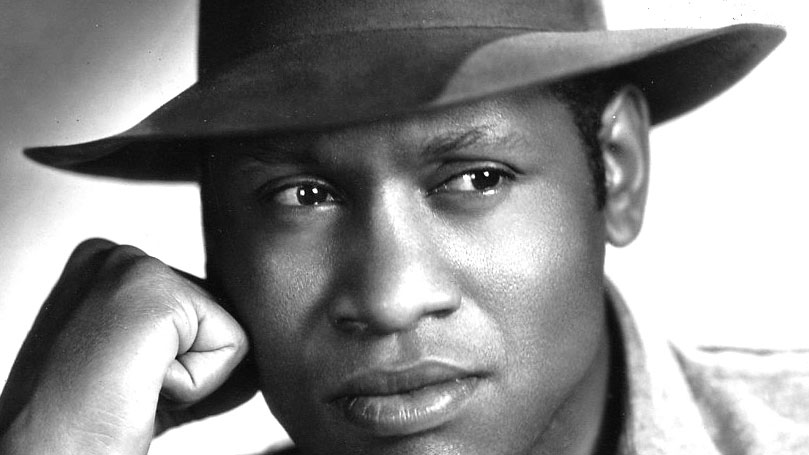

Gerald Horne has produced a powerful and thoroughly researched biography of one of the most prominent leaders of the twentieth century Civil Rights movement. William Patterson was born in California in 1891 to a mother who had herself been born in slavery and a father born on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent. Patterson would become one of the most widely known and influential African Americans in the country and perhaps the world by the mid 20th century. He would experience some reverses, including a three year prison term during the Cold War period, but would continue his political activism and his Party leadership until his death in 1980.

In fact, it was at the 20th Century’s midpoint that Patterson would make one of his most momentous contributions when he led the effort, did much of the research and presented the “We Charge Genocide” petition to the United Nations in December 1951.

Trained as a lawyer who could have pursued a lucrative career in private practice, Patterson chose a different path. Attracted to radical politics in his youth through his West Coast activities and after traveling to Central America and across the US, he met Marxists and Communists, including Paul Robeson, in New York City. For a time he did legal work for the NAACP. In 1927 he took a bus with other activists to Boston to demonstrate against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. He would later say that the experience—and the failure to save their lives– changed his life. He would devote the rest of it to the Communist Party and the struggle against racism and for working class unity.

In the late 1920s Patterson went to Moscow along with other US radicals, Black and white. Here he experienced intense—and sometimes rough and tumble political debate—especially about what was then sometimes called the Negro question—a topic which was getting much attention in the young USSR. Here he came to view racism in the USA as part of a global challenge and the peoples living under European colonial rule as the allies-in-struggle of Black Americans.

In the USSR he also married a Russian woman and fathered two daughters. They would grow up, be educated and have careers in the Soviet Union. The contacts and outlook he developed during his time there would prove crucially important as his long and influential career continued.

Scottsboro and the 1930s

The series of events that took place during the early 1930s, as the Great Depression was taking hold, saw Patterson, the CPUSA, and organizations that it started or helped to build gain wide influence and considerable prestige in the US and abroad. The case of the Scottsboro Nine was not the only case of Jim Crow “justice” that got the Party’s attention during this time, but, Horne argues, it was the case that “catapulted” the Party into the national and indeed the international spotlight. This was the case that saw the CPUSA out-flank and out-organize the NAACP and, in fact, for a while gain the grudging respect and co-operation of some leading members of that older body.

Horne argues that the organization that became “the tip of the spear” in the campaign to save the nine young African American men (and boys) in Alabama was the International Labor Defense (ILD) which had, itself, been organized by Big Bill Haywood and others who had also spent time in Moscow. When the ILD took up the Scottsboro defense it meant that this case in “a rural Alabama backwater” would become a globally recognized issue that would embarrass the US State Department and force the nation’s leaders to begin to give reluctant attention to Jim Crow and the plight of the nation’s citizens of African descent.

The case would also confirm the Party’s stature as the leading organization willing to take the burning question of Jim Crow in the US from the courtroom to the streets and to the world. Horne quotes an FBI memo to the effect that Scottsboro “was the first big battle conducted by the Communist Party USA among Negroes and was used by them as a stepping stone to penetrate broad masses of the Negro people and to extend Communist influence among them.” (p. 43) The Scottsboro case would also expose the split and leave lasting marks on the relationship between the CP and the NAACP. According to one source, NAACP head Walter White actually showed contempt for the defendants and their parents, all from poor backgrounds and “betrayed prejudices against blacks [sic] who were not from the middle class.”

The Black Belt thesis and changing times

The Black Belt thesis held that, since African Americans constituted either a majority or a sizable minority in a swath of territory across much of the South, they were entitled to an independent “republic” or some political entity of their own in that area. While this thinking never replaced the more concrete goal of fighting against Jim Crow laws “on the ground”, it persisted as a longer term goal during much of the period of the ‘20s through the ‘40s and was clearly influenced by the Soviet experience.

According to Horne, the shift away from this notion (always controversial) occurred during the period immediately after WWII and was a part of (or was accompanied by) a vigorous larger debate in the Party concerning the role and actual existence of the Party itself.

Earl Browder argued that the WWII experience of broad anti-fascist popular front activity and the victory over Nazi Germany would usher in a period of co-operation that would allow the CPUSA to dissolve or at least change its character and become a lobbying association or something similar. As it became apparent that this view did not reflect the post war reality and that corporate and reactionary forces were moving forcefully to reassert power and influence they felt they had lost during the years of the New Deal and FDR, the CPUSA underwent intense internal debates. How should this new situation be confronted?

Under these circumstances, it soon also became clear that the renewed reactionary assault would include not only an attack on organized labor, but an intense focus on the Jim Crow landscape as well. Racist rhetoric in many commercial press outlets intensified, and lynchings and other instances of terror against African Americans persisted with frightening frequency.

“We Charge Genocide” and the post World War II “bargain”

This was the moment that Patterson and Robeson along with some others who stuck with them during this time of greatest trial (unlike some on the left and in the Black community) chose to present the We Charge Genocide petition to the United Nations. This effort was, in fact, the result of years of preparation and thought on Patterson’s part, and the petition was painstakingly enough researched to impress many legal scholars and others who actually took the time to read it. Independent left-wing journalist I.F.Stone backed the petition, saying ”to browse through pages 57 to 191 of the genocide petition is an experience for any white man.”

The petition was presented simultaneously in Paris by Patterson and in NYC at the UN by Paul Robeson. It generated wide spread interest around the globe and got support from socialist countries, from the colonial world and in western European countries as well.

As Horne persuasively argues, the petition both embarrassed and infuriated powerful forces—Dixiecrats and others—in the USA. The decade of the 1950s saw the beginning of the crumbling of the “legal” edifice of Jim Crow with the Brown decision of 1954 and ensuing Civil Rights legislation. They were the result both of long struggle and much risk and sacrifice at home in the US and of the world wide pressure generated by the efforts of Patterson and others over many years.

The retreat from Jim Crow, Horne suggests, was part of a rough “bargain” that Cold War conditions forced on the US Government: the legal edifice of segregation would come down, but those who had led the battle against it would get none of the credit. They would, the script went, be marginalized (or worse) and forgotten.

As Horne makes clear, to his credit (and to Patterson’s), that is not quite how things worked out. In his later career, “after suffering through years of imprisonment, investigation, surveillance, and harassment” and approaching the age of 80, Patterson did important work, for a time, in support of the Black Panther Party and played a key role in building and organizing the defense of Professor Angela Davis. His stature and influence in the broader Black liberation movement were illustrated by the support he was able to gather from prominent personalities, such as Ossie Davis, Ralph Abernathy and Dick Gregory, during the turbulent period of the late 1960s and early ‘70s.

A worthy complement to Horne’s most valuable Black Revolutionary is Walter Howard’s We Shall Be Free, an annotated collection of original documents by seven leading African American Communists, including Patterson. Howard includes a section of the 1951 petition to the UN charging the US Government with genocide against the “Negro people”, supported by documentary evidence and based, as the petition states, on the Genocide Convention adopted by the UN General Assembly in December 1948. Together these two books make a most welcome contribution to the literature on the CPUSA, the American left and the struggle for racial progress during the twentieth century.

For those interested in digging farther into this too-often neglected history, the miracle of electronic communication offers some interesting options. I was able to get my hands on an early copy of the genocide petition published in 1951 by the Civil Rights Congress. Also, Patterson’s autobiography, The Man Who Cried Genocide, which has more information about his early life, was published by International Publishers in 1971 and reissued in 1991.

Join Now

Join Now