The following is based on a contribution to a recent conversation sponsored by the Communist Party of Britain on the rise of the far right. Vijay Prashad from TriContintental also participated.

There’s a long history of populism in the U.S. going all the way back to the late 19th century. My first acquaintance with that populist sentiment came from stories our grandmother told us. One of her favorites was about the time when her father, who was a Black Alabama coal miner, went out on strike in a rural community called Patton Junction around the time of World War 1.

And the story went like this: the miners struck, the company tried to break the strike, there was a gun battle, and the company got the worse of it. Governor Thomas E. Kilby, then sent in 500 National Guard troops by train to break the strike. But the poor whites in the next county cut the railroad tracks, and the miners were able to escape. You see, there was a common — I guess you’d call it populist — disdain amongst the Black miners and the poor white farmers for what Paul Robeson used to call “big white folks” — even in Jim Crow Alabama.

Well, we shouldn’t be surprised, because populism back then was quite in force in Alabama. For example, in the 1890s, the People’s Party wiped out the Democrats in a number of Alabama counties. And this movement wasn’t just limited to Alabama. In 1894, they took both houses of state government in North Carolina and elected some 47 state representatives in Georgia.

Now, I’ve been trying to figure out whether this was a right-wing movement, or centrist, or was it left, or do those categories as defined today even make sense when applied to the situation back then. And while populism may be considered a form of class consciousness, it’s been marred from the start by the ideological imprint of slavery, segregation, and ruling class racism.

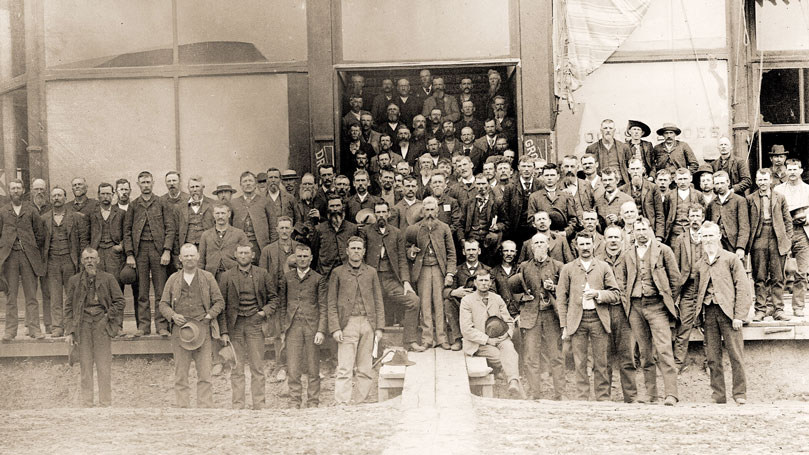

The populist movement got its start amongst farmers in Texas who founded an organization called the Farmer’s Alliance. The Alliance had two “branches,” one white, the other African American — such was the racist legacy of the antebellum South. The People’s Party was founded in 1891. From their earliest beginning they formed alliances with labor and tried to persuade Eugene Debs to be their standard-bearer in 1892. They supported nationalization of the railroad and a shorter work week. The People’s Party had a big presence among women and advocated for the women’s vote. However, like its precursor, the Farmer’s Alliance, the People’s Party was also segregated: officially so. They even conducted segregated public schools. So was it left, right or centrist?

It’s an important question because segregation proved to play a huge role in its undoing. Consider that back then the populist movement made major gains in every single Southern state with the exception of Mississippi. And in every single state after those victories, the Democratic Party — which was the party of white supremacy — rallied to defeat them and made sure they stayed defeated by imposing Jim Crow laws, including poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests to prevent both Blacks and poor whites from voting.

As the article “The Forgotten Career of Jim Crow” states, “No disenfranchisement law was passed in any Southern state before the state experienced a successful electoral insurgency from either the Farmers’ Alliance or the Populist Party, save for Mississippi, whose legislature acted preemptively and whose laws were mimicked throughout the South following the Populist insurgency.”

By the turn of the century, they succeeded: most Black and poor whites couldn’t vote. And that remained true, until the Civil Rights movement compelled the passing of the Voting Rights Act in 1963.

Racism remained a major factor in many social movements in the U.S. of the last century: It infected the Socialist Party of Eugene Debs, which was also segregated; nationalist reactions to racism helped spark Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement which had populist features; racism was a major presence in Huey Long’s populist governorship of Louisiana in the 1930s.

Racism, along with anti-Semitism, was a central feature of a very popular 1930’s radio personality by the name of Father Coughlin. Father Coughlin supported nationalization of industries, labor rights, and founded an organization called the National Union of Social Justice, all the while, claiming that Jewish bankers caused the Depression and that the Nazis were justified in the pogroms following Kristallnacht. So, again, were his views left, right, or center? And what’s the criteria for making a determination?

A review of the rest of the 20th century reveals that populist insurgencies had established quite a base and appeared in various iterations like Barry Goldwater’s John Birch Society-supported run for presidency in 1964, followed by arch segregationist George Wallace’s similar bid in 1968. Wallace secured 13 percent of the popular vote and won 5 Southern states.

And then there was Ross Perot’s independent candidacy in 1992. Mr. Perot prefigured Trump in many ways, including America First-like rhetoric, opposition to NAFTA, and calls to “clear out the barn” in D.C. Perot won 19 percent of the popular vote.

Segregationists’ “pro-life” strategy

Now you might ask, what has this to do with what’s called 21st century populism in the U.S.? And I would answer everything. You see today’s MAGA movement has its roots in a severe swing to the right in the Republican Party in the 1970s and 80s. This shift is associated in people’s minds with the GOP’s Southern Strategy, the rise of the Moral Majority, and its opposition to abortion. But that’s only partly true. It’s actual “birth” — if you’ll pardon my use of the word birth — was prompted not by abortion, but by a federal decision to end tax exempt status to segregated Christian schools in the South.

These schools arose in response to the outlawing of segregated public education by the Supreme Court in 1954. What is today called the religious right started as a movement to maintain white supremacy in the South and to prevent Black students from meeting white students at school — marrying and having, God forbid, little Black babies.

It was tactically challenging to develop mass public support for maintaining Jim Crow. But saving the unborn from “mass murder” was another thing entirely.

Opposition to abortion came later. You see it was tactically challenging to develop mass public support for maintaining Jim Crow after the Civil Rights movement’s successes. But saving the unborn from “mass murder” was another thing entirely. And so the Protestant right formed an alliance with Catholics of many persuasions and the Christian right was born. Significantly, all of this occurred at the behest of the Chamber of Commerce and the National Committee of the Republican Party.

Economy-fueled dangers

Tax exemption for Christian schools and abortion were only two of the major issues that helped fuel the anger and resentment that helped form the coalition that makes up today’s Republican Party. We also must stress the collapse of basic industry in the Midwest and elimination of hundreds of thousands of jobs. Then there was the farm crisis in which thousands of family farms went bankrupt because of high interest rates and were gobbled up by agribusiness. Add to the list NAFTA and other trade agreements that resulted in the export of jobs and capital out of the U.S. And of course, we can’t forget the neoliberal policy engineered by the GOP and implemented by the Democratic Party as well in all of the above. After all this came the financial storms of 2007 and 2008 and the Great Recession that almost brought down the world economy as result of speculation on subprime loans to Black and Latino families.

Now all of these served as fodder for organizing drives by the far right and the rise of patriot networks. Many of them responded by forming armed militias. Their professed goals were to dismantle almost all aspects of government regulation of the economy, such as the minimum wage and environmental regulation, as well as civil rights guarantees for historically oppressed groups. We’re talking about the Armed Citizens Militia movement, the Three Percenters, the Sovereign Citizens, and the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association.

There were some 200 militia units by the mid-1990s, with between 20,000 and 60,000 active participants at its peak. The broad Patriot movement influenced as many as five million Americans. It’s reported there were 1,371 active hate and anti-government extremist groups in our country last year, among them the Proud Boys, the Oath Keepers and so on.

It’s reported that these groups intermingled with and formed working relationships with other right-wing movements, in the first place, what was known as the Tea Party. In fact, by 2015, the Tea Party grassroots was heavily populated by organized white supremacists. Donald Trump’s bid for the presidency around the same time served as a vehicle for these forces who merged into the MAGA coalition. Witness, for example, the rise of Steve Bannon who helped form both the Tea Party and the now infamous alt right. Bannon went on to become Trump’s campaign manager and then served in the administration until the two had a falling out. He was later rehabilitated and now plays a supportive ideological and organizational role with his War Room podcast, established during the pandemic. This helped Trump and Co. dust themselves off and regroup after their defeat in 2020.

And that’s a story that needs to be told, including the marshaling of support from tech right figures like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk, the organization of Project 2025, the role of the Heritage Foundation, and the deepening of support from sections of the labor movement.

The religious right

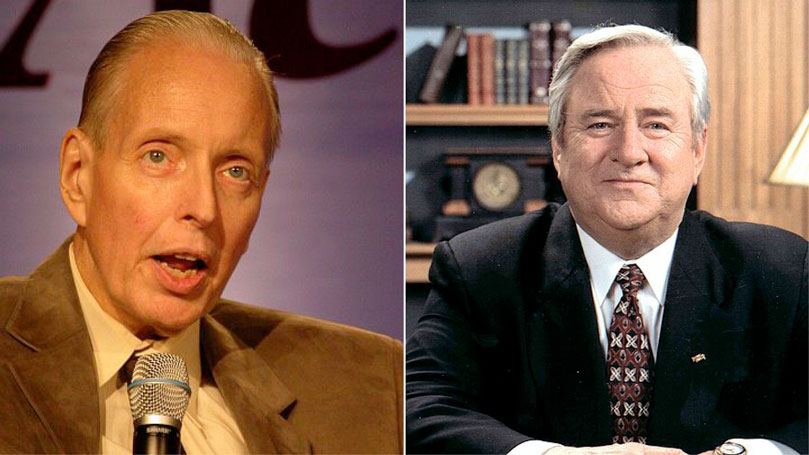

For the purposes of this discussion I want to focus briefly on the part played by the religious right, the Heritage Foundation, and the figure of Paul Weyrich, who was its co-founder. He, along with Jerry Falwell were the ones who mobilized the Christian right on the issue of tax exempt status for segregated Christian schools. They then led these forces in the campaign to overturn Roe v. Wade.

It is important to take note of two significant developments. First, white evangelicals now dominate the overwhelming majority of people who call themselves Republicans. Studies have shown “there is essentially no difference between a Republican who is white and born-again and a Republican in general … For the past decade there has been no daylight between white evangelicals and the GOP.”

Now, while you’re thinking about that, think about this: a new force, who call themselves Christian Nationalists, has emerged within these evangelicals who now dominate the movement. The Christian Nationalists hold that the U.S. is a nation by and for Christians alone and a certain type of Christian at that. And it won’t surprise you that those are white Christians alone. In other words, Christian nationalism is a movement about white identity, that is, white supremacy. Notwithstanding their expressed racism, in surveys they express most hostility not to immigrants, or Muslims, but to socialists and communists. Their ideologues openly promote views about power, hierarchy and greatness drawn from the vocabulary of fascism. A key figure in this Christian Nationalist movement is Russ Vought, who heads the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Vought comes out of the Heritage Foundation and is one of the main authors of Project 2025.

Now a word of caution. The point here is that not all or even most Christian evangelicals are Christian nationalists, but rather that in their minds, and in the minds of the broader public, there’s no distinction between the two. And with Christian nationalists now dominating the commanding heights of the religious right and indeed the U.S. government, a very dangerous situation has emerged. All of this is occurring within the framework of MAGA and what’s called populism.

Fascist danger

Here I’ll end where I began: what is this thing called populism and where does it stand on the ideological spectrum? And by what criteria is it assessed? And do those criteria change with the movement of history? Certainly we would not judge the populist sentiment of the early 20th century by the standards of today. Today you could not credibly call a movement that advocated apartheid left wing, could you? In fact, today, any movement that represented itself as left but promulgates nationalist politics in the developed capitalist countries — and there are some — we’d say were guilty of a red–brown abomination, wouldn’t we? That’s been true ever since Mussolini marched on Rome and the rise of the Nazi Party.

I would say that in the U.S. today there’s a credible fascist danger. It reveals itself in the growing lawlessness of the Trump administration in pursuit of its Project 2025 objectives, a platform whose architects are Christian Nationalists flirting with, if not openly, embracing fascist ideas: white supremacy, eugenics, and social engineering. And then there’s the influence of the tech right who harbor some of the same notions.

So, right-wing populist? Maybe. Fascist? They are moving in that direction. But in our view in the U.S., it’s so important to have a clear idea and definition of what we’re talking about, which is why I rebel at descriptors like “authoritarian” and “populist” to describe MAGA and Trump. There seems to be no class analysis here, no accounting for the various social forces in contention and their responses to the deepening crisis prompted by the pursuit of maximum profits.

After all, that’s what got the country into this mess with NAFTA, the subprime crisis, and the TPP. And then there’s the new attempts by U.S. imperialism to reassert itself in the face of stiff competition, and hence the support of both parties for the genocide in Gaza, the expansion of NATO and the war in Ukraine, along with the new Cold War against China.

So are we on the path to a New World Order? Well, it’s clear that notwithstanding a consensus of the two major parties on some issues, there’s no agreement on others. It’s also clear that with Trump and MAGA there’s a new aggressiveness in sections of the U.S. ruling class with all the talk of making Canada the 51st state, seizing Greenland, and taking over the Panama Canal.

The Trumpsters clearly have very different views than the neoconservatives and the Democratic liberals on NATO, Russia, and the international order established after World War II. But whether these differences will be mitigated remains to be seen. The inter-class battle for hegemony among different ruling factions is not over, and estimates of a permanent major shift by Fukuyama and others I think are overstated. I don’t think Trump has achieved a permanent governing majority. Indeed, the shape of things to come depends in large measure on the outcome of the current domestic struggles over the implementation of the Trump agenda and immigration in the first place. How that will play out is uncertain, and that includes the midterm elections. We don’t know what’s going to happen.

The danger of fascism, however, is clear and present. Frankly speaking, we were startled by the raging silence in the country after the election. We were even further taken aback by the capitulation of important sections of civil society: the universities, the mass media, law firms, and so on. We asked ourselves: what just happened?

The resistance

But the good news is that in spite of these challenges, the resistance has been growing in strength, with the boycotts of Tesla, Target, and Amazon, the huge demonstrations in particular on April 5th, and as last Saturday’s several-million-strong “No Kings” demonstration attest.

The anti-MAGA coalition is beginning to find its footing. It’s still somewhat tentative. There remain deep divisions. And labor — which is decisive — has yet to make its presence felt in a significant way. As we know, the ruling class only understands one language and that’s the language of power. Until labor takes a stand and flexes its muscles, Trump’s march will go largely unchecked.

But things are moving, and with that comes hope. At the end of the day, it is clear that domestically, we’ve reached a turning point moment; or maybe it’s more accurate to say we’re between two moments. But a new progressive governing majority, while hopefully on a future horizon, depends on things that are not yet in place, like radical reforms of the electoral system.

To us, a new third party needs to emerge. But the main thing now is that we have to fight with the vehicles that we have, not the ones we want, to break the grip of MAGA on the government. Again, things are moving, and with that comes hope.

Images: 1. Jan. 6 insurrectionists unfurl their Christian nationalist orientation. Jesus 2020 by Brett Davis on Flickr. (CC BY-NC 2.0) 2. The 1890 People’s Party candidate nominating convention in Columbus, Nebraska, where Omer Kem was nominated for Congress by Solomon D. Butcher, digitally edited by Tim Davenport. (public domain photo via Wikipedia / Library of Congress). 3. Right: Segregationists protest the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1959. Protesters carry U.S. flags and signs reading “Race Mixing is Communism” and “Stop the Race Mixing March of the Anti-Christ.” (Library of Congress via picryl.com) Left: A participant of the 2025 anti-abortion March of Life in Virginia by American Life League on Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0) 4. Left: Heritage Foundation co-founder Paul Weyrich (Wikipedia) Right: Lynchburg Christian Academy founder Jerry Falwell Sr. (Wikipedia) Weyrich and Falwell mobilized the Christian right on the issue of tax exempt status for segregated Christian schools. 5. No Kings demonstration on June 14, 2025 (CPUSA)

Join Now

Join Now