To understand the effects of colonialism on the daily lives of working-class Puerto Ricans, especially the Puerto Rican diaspora community residing in the United States, Jesús Colón’s seminal work A Puerto Rican in New York, and Other Sketches provides invaluable insight. This book is a collection of stories — mostly anecdotal sketches from Colón’s life as an Afro-Puerto Rican living in New York City from the 1920s to the late 1950s. Through these sketches, Colón teaches his readers about multiracial working-class consciousness, Puerto Rican independence, anti-racism and anti-colonialism, international working-class solidarity, and the importance of education, literature, and culture. Originally published in 1961, the book features selections from Colón’s column in the Daily Worker, along with previously unpublished pieces.

Colón describes the book as a “modest attempt by a Puerto Rican who has lived in New York many years — always among his people” — to share with wider American society “how Puerto Ricans in this city really feel, think, work, and live.” In the preface, he asserts that “Very little has been written about the Puerto Rican in New York City.” He notes that voluminous studies and official reports, framed as “The Puerto Rican Problem,” reduced Puerto Ricans to “statistical ups and downs on municipal charts… often left to gather dust in the archives.” Even “fabulously successful” musicals like West Side Story remained “out of context with the real history, culture and traditions” of Puerto Ricans. Thus, Colón’s book offers an essential lens on the Puerto Rican experience, advocating for national independence and socialism as the path toward freedom for the island and its people.

Colón’s sketches shed light on his own trials as a man of color, a worker, and a communist, while also painting a composite portrait of Puerto Rican communities through varied characters, historical vignettes, and social critique. His integration of communal history with individual experience opens new worlds to his readers. It also reflects his working-class approach to subjectivity, always placing his own life in relation to a broader collective. He blends narratives of self with the shared experiences of oppressed peoples, the Puerto Rican community on the island and in the diaspora, and workers worldwide.

To cultivate global working-class consciousness, Colón educates readers about U.S. imperialism in Latin America, anti-Black and anti-Puerto Rican racism in the United States, and Latin American heroes like Simón Bolívar and Puerto Rican feminist Ana Roqué de Duprey. Colón also planned a second collection titled The Way It Was: Puerto Ricans from Way Back, intended as a historical record of the first generation of Puerto Rican migrants in New York. Though unpublished before his death, these works were released posthumously in the early 1990s as The Way It Was, and Other Writings. Many consider Colón the “father” of the Nuyorican cultural movement of the 1960s and 70s.

Born in 1901 in Cayey, a rural mountain town in Puerto Rico, Colón grew up amidst a booming tobacco industry and expanding U.S. commercial influence. In the first story, “A Voice Through the Window,” he recalls watching about 150 cigar makers in a local factory listen intently as el lector (the reader) read aloud from newspapers, working-class weeklies, or novels by Zola, Hugo, or Karl Marx. This 19th-century practice helped transform cigar workers into one of the most socially conscious sectors of the working class, known for organizing labor movements, leading independence struggles in Cuba and Puerto Rico, and championing socialism and international solidarity.

Growing up in this milieu of radical labor organizing and working-class education instilled in Colón a love of literature and learning and critically shaped his political consciousness. “The workers and the cigar makers taught me,” Colón wrote. “They gave me pamphlets and papers to read — they told me that we were a colony — a sort of storage house for cheap labor and a market for cheap industrial goods… And that not until colonialism was wiped out and full independence given to Puerto Rico would the conditions under which we were living be remedied.”

Colón’s perspective was further shaped by leading a student strike, writing for his school’s magazine Adelante, and witnessing striking workers violently attacked by mounted police in San Juan. “Nothing in those schoolrooms… has taught me as much as that encounter between the workers and the police that eventful day,” he writes in “The Way to Learn.” Advocating for both independence and socialism, Colón links education with international working-class solidarity: “In the end, if we keep on struggling and learning from struggle, the workers and their allies will win all over the world.”

Making his way to New York City in 1918 as a stowaway, Colón worked various jobs to survive alongside his brother. In stories like “Easy Job, Good Wages,” “Two Men with But One Pair of Pants,” and “How to Rent an Apartment Without Money,” he recounts their early years of hardship. Colón worked as a cigar maker, postal worker, and dock laborer and involved himself in labor struggles throughout his life. He became a correspondent for “Justicia” (organ of the Puerto Rican Federation of Labor), founded the Socialist Party’s Puerto Rican Committee, and was active in the Puerto Rican Workers Alliance and the Hispanic Workers’ Atheneum of New York.

Colón always made time for political and cultural activities — community organizing, grassroots activism, reading, teaching, and writing — seeing them as critical for a higher quality of life and true social emancipation. He joined the Communist Party USA in 1933 and remained an active member and leader until his death in 1974. He taught at the CPUSA’s Jefferson School of Social Science, led the Cervantes Fraternal Society of the International Workers Order, and wrote for Spanish-language newspapers like Pueblos Hispanos and Liberación.

Living in New York for decades, Colón experienced the discriminatory housing, employment, and criminal justice systems confronting Puerto Ricans in the early 20th century. His stories document the formation of his class consciousness. In “On the Docks it was Cold,” finding an old work badge triggers memories of his time as a dock and rail-yard worker. He describes the feats of strength and coordination among workers and recalls foremen like Mr. Clark, born in Panama to Jamaican parents, who was respected for his knowledge and linguistic skills.

As a working-class scholar, Colón saw the people he encountered as knowledge holders whose skills and intelligence contributed culturally and materially to society. He often “jumped scale,” linking everyday local contexts to global struggles. Wondering if Mr. Clark’s father helped build the Panama Canal, Colón theorizes the relationships between local social encounters and global systems of capitalism, racism, and imperialism. He examines how power structures impact the “little things” of daily life: riding the subway, walking down the street, going to work, or eating at a restaurant.

Colón’s use of the sketch form creatively relates personal anecdotes to history and social issues, engaging readers to see their own lives as part of a shared struggle for democracy, equality, and justice. For him, the old work badge symbolized “the millions of men and women on the seas and in the fields… who risk and lose their lives… one day in these United States the workers will ask themselves collectively: ‘For whom all this toil? For what?’ And their collective answer will be heard around the world.”

From 1955 to 1968, Colón wrote the column “As I See it From Here” for the Daily Worker and its weekly version, Worker. He also contributed to Mainstream and wrote “Puerto Rican Notes” for the Daily World. Some of these articles highlight Colón’s connection to Latin American figures, like Afro-Cuban General Antonio Maceo or muralist Diego Rivera. He exposed injustices under U.S.-backed dictators like Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic, arguing such regimes were “coddled and protected” by Washington.

In “Pisagua,” Colón alerted readers to a concentration camp in Chile where labor leaders and intellectuals were imprisoned for opposing the joint exploitation of Chilean reactionaries and American imperialism. His writings linked U.S. support for Latin American dictators to the erosion of democratic rights at home. Reflecting on the seizure of the Daily Worker offices by federal agents, Colón warned that such events “should be a lesson for those… telling themselves that things like the closing of daily papers could not happen in this country.”

Colón also connected the denial of civil rights to Puerto Ricans with racism against African Americans. In sketches like “Hiawatha Into Spanish,” “Little Things Are Big,” and “Because He Spoke in Spanish,” he reckons with his own experiences as a Black Puerto Rican. Once, after earning a promotion for a translation, he arrived at the office only to be told, “That was to be your desk and typewriter. But I thought you were white.” In another story, he hesitates to help a white woman with her children late at night in a subway station, fearing her potential prejudices. He laments being frozen into inaction by the racial climate, moving on “as if insensitive to her need.”

He narrates being called a racial slur by a child in a restaurant and the murder of a young Puerto Rican veteran, Bernabé Núñez, for speaking Spanish. Colón condemned this “out and out discrimination” and called on readers to join community organizations. “To rid society of racist reactionaries,” he declared, “we have to organize the broad forces of decency… and not be silent wherever we are.”

As a Puerto Rican, Colón demanded greater recognition of his community’s contributions. In “Wanted – A Statue,” he notes that while other ethnic groups had public monuments, there was “not one statue of a Puerto Rican in all the marble and bronze figures in the city.” He argued for a monument placed not in Puerto Rican Harlem but “in the very heart of the city” as a symbol “full of beauty and dignity as the life we are building together with the rest of our brother New Yorkers for a future of freedom and abundance for all.” For Colón, its purpose was to remind everyone “that in every people there exist the spark and inspiration to do and to produce great deeds and great works.”

In stories like “The Library Looks at the Puerto Ricans” and “How To Know the Puerto Ricans,” Colón challenges readers to learn from colonial peoples who have “much to teach” from their struggles. He also critiques traditional institutions of knowledge, advocating for better representation of Puerto Ricans in library collections. To truly know Puerto Ricans, he invites the reader to “come to knock at the door of a Puerto Rican home… prove yourself a friend, a worker who is also being oppressed by the same forces that keep the Puerto Rican down.” Understanding, he believed, required appreciating “their history, their culture, their values, their aspirations for human advancement and freedom.”

Colón’s writings blend elements of José Martí’s Crónicas with the humor journalism of Mark Twain. This hybrid style — neither straight journalism nor fiction — allowed him to intimately connect with readers. Using literary montage, he pieced together personal reflection, historical narration, journalistic reporting, and lively characters, with tones ranging from ironic humor to somber pensiveness. This approach established trust with his audience, making his work profound yet accessible and relatable.

Colón motivated his readers to see themselves as part of a larger collective capable of effecting transformative social change. For him, a just world would arrive when “the factories and the earth on which they are built will be given back to their rightful owners: The farmers and the workers of the hand and brain. They are the ones who make anything worthwhile in this world.”

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

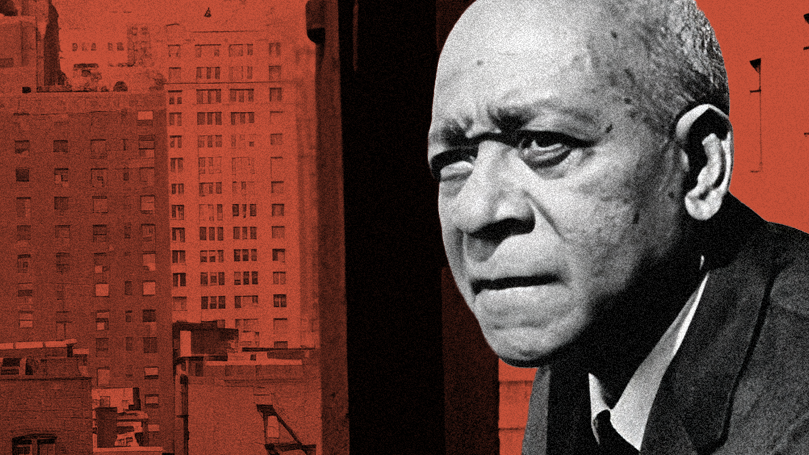

Images: Jesus Colon, circa 1973, Jesus Colon Papers / Center for Puerto Rican Studies. Fair use.

Join Now

Join Now