The opioid crisis lies at the intersection of two public health challenges: reducing the burden of suffering from pain, and the rising toll of harms related to opioid use.

—Report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017

Decriminalization is important, because it introduces a lot of coherence in the system. If you address the problem as a health condition, it makes little sense to criminalize this kind of behavior. . . . You don’t criminalize a diabetic because he eats too much sugar, or a cigarette smoker. Even with what can be considered a self-inflicted disease, the state assumes the responsibility to contribute to a better life of its citizens.

—João Goulão, MD, architect of Portuguese drug policy and Director-General of the Service for Intervention on Addictive Behaviours and Dependencies, Ministry of Health

Beneath the COVID-19 pandemic lies the ongoing and worsening crisis of opioid overdose and death. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate “an estimated 100,306 drug overdose deaths in the United States during [a] 12-month period ending in April 2021, an increase of 28.5% from the 78,056 deaths during the same period the year before.” Drug overdose deaths have accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This crisis has touched every corner of the United States. Demographic data vary by region, but no group has been unaffected. Blacks, Hispanics, Whites, Asian Americans, and Native Americans of all ages and income have suffered from drug use, addiction, overdose, and death. The CDC outlines three waves in the history of the opioid crisis: a first wave coinciding with an increase in prescription opioid deaths beginning in the late 1990s, a second wave of opioid deaths related to heroin overdose, and a third wave beginning in 2013 related to a rise in synthetic opioid use, particularly fentanyl.

The human toll is immense. Between 1999 and 2019 nearly 500,000 people died from opioid overdose. Opioid use has been cited as a factor in at least 7 out of every 10 overdose deaths. More than 2 million cases of hepatitis C and 1 million cases of HIV/AIDS are attributed to intravenous drug use. The opioid crisis has even led to increases in human trafficking cases. Moreover, the CDC estimates that “the total ‘economic burden’ of prescription opioid misuse alone in the United States is $78.5 billion a year, including the costs of healthcare, lost productivity, addiction treatment, and criminal justice involvement.”

Origins of the crisis

To describe the opioid crisis as a public health emergency is an understatement. It is a collective ethical failing by this country and its institutions. The opioid crisis arose and developed from multiple sources. Healthcare workers and hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and government agencies and politicians are collectively responsible for the hollowing of communities across the country.

The opioid crisis originates partly from a desire to address the burden of pain. Pain is multifaceted and has components that are physiological, emotional, social, and cultural. Moreover, chronic pain is a cause of disability and a source of substantial mental health burden. Prior to the 1990s, opioids were generally prescribed to manage acute, cancer-related pain. Beginning in the 1990s, pain management practices shifted. Opioids were increasingly being used to manage chronic, non-cancer pain. Clinical guidelines at the time cautioned the expanded use of opioids and advised that opioids be used discriminately. Pharmacologic treatment should have occurred together with behavioral and psychological care in a multidisciplinary approach. Yet, what ultimately developed was a narrow, unimodal model of care with reliance on pharmacologic solutions to pain. The fragmented landscape of health insurance and access to care in the United States together with costs generally prohibiting multidisciplinary medical practices encouraged this development.

The opioid crisis originates partly from a desire to address the burden of pain. Pain is multifaceted and has components that are physiological, emotional, social, and cultural. Moreover, chronic pain is a cause of disability and a source of substantial mental health burden. Prior to the 1990s, opioids were generally prescribed to manage acute, cancer-related pain. Beginning in the 1990s, pain management practices shifted. Opioids were increasingly being used to manage chronic, non-cancer pain. Clinical guidelines at the time cautioned the expanded use of opioids and advised that opioids be used discriminately. Pharmacologic treatment should have occurred together with behavioral and psychological care in a multidisciplinary approach. Yet, what ultimately developed was a narrow, unimodal model of care with reliance on pharmacologic solutions to pain. The fragmented landscape of health insurance and access to care in the United States together with costs generally prohibiting multidisciplinary medical practices encouraged this development.

Physicians and hospitals also faced pressure from the government to address pain. It is well documented that physicians historically under-treated pain. Additionally, evidence suggests that implicit racial bias among medical students and physicians affects both the assessment and treatment of pain. Yet, a number of regulatory interventions meant to improve the treatment of pain help set the opioid crisis in motion. Examples include the documentation of pain on health records as the “fifth vital sign,” overemphasizing pain as a quantifiable measure, and the inclusion of questions related to pain in patient satisfaction surveys that serve as a proxy for quality. Hospitals are required to submit these surveys or incur a penalty in their reimbursement by Medicare. The focus on quantifying pain and tying it to reimbursement incentivized quick and easy solutions — for example, increased prescribing of opioids.

The introduction of well-intentioned measures to try and correct a shortcoming of medicine should be contrasted to the entirely profit-driven motive of the pharmaceutical industry. The pharmaceutical industry encouraged and manipulated the desire of physicians and other medical professionals to address patients’ pain. For example, Purdue Pharma, the makers of OxyContin, spent millions of dollars reassuring physicians, elected representatives, and the public that oxycontin was safe and non-addictive. The company also purposefully manipulated and misrepresented research to boost their sales. This “commercial strategy” continued even after Purdue Pharma was convicted of misleading regulators and physicians in 2007. Earlier this year Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to fraud and giving illegal payments to prescribers.

Solutions

The alarming rise in opioid deaths demanded solutions. One popular solution was the implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs to track the number of prescriptions written and filled. While successful in decreasing the total number of opioid prescriptions and identifying “pill mill” doctors, a consequence of these programs was shifting opioid use from prescription drugs to heroin. Heroin — and, later, synthetic opioids like fentanyl — became cheaper and easier to obtain than prescription opioids partly as a consequence of these regulations.

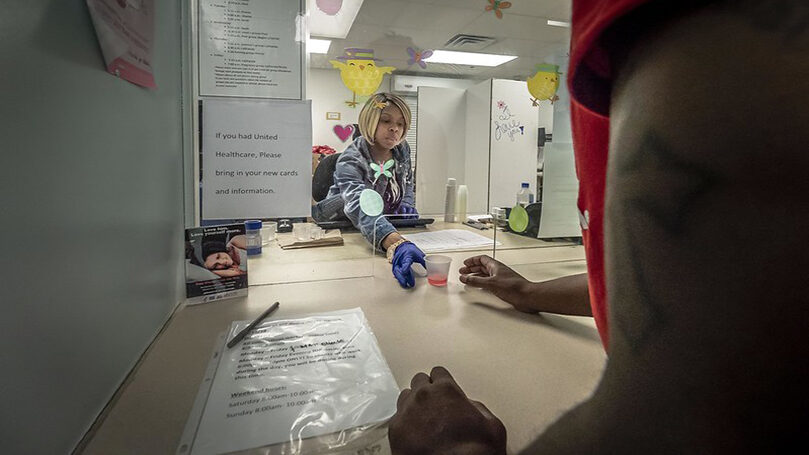

A wealth of evidence highlights the efficacy of medication-assisted treatment, which combines pharmacologic treatment to address the physiological manifestations of withdrawal with behavioral therapy to address the psychological components of addiction. Heightened scrutiny of prescribing practices also limited physician autonomy and discouraged medication-assisted treatment (MAT, or MOUD — Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorders). Physicians justifiably worried of being flagged and disciplined for prescribing opioids used in MAT, such as methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, by prescription drug monitoring programs.

There are success stories from which we can draw lessons. Throughout the 1990s Lisbon, Portugal, was known as the heroin capital of Europe, with hundreds dying from opioid overdose each year. Typical repressive policies did not stem the spread of Portugal’s drug crisis. Rather, changes in societal attitudes toward drug use and addiction are ultimately credited with solving the country’s drug crisis more than legislative reforms. Addiction was treated as a complex medical and social challenge rather than an individual moral failing requiring police repression and incarceration as deterrents. “Junkies” became known as “people who use drugs” or “people with addiction disorders.” Proper funding and public support for treatment options and harm reduction approaches resulted in dramatic declines in HIV and hepatitis infection rates and drug-related crime rates. Portugal’s success in turning its own opioid crisis around demonstrates the efficacy of public health measures focused on decriminalization, harm reduction, and multidisciplinary healthcare.

Unfortunately, policymakers here in the United States have not fully embraced this view. Legislative efforts have been uneven and half-hearted, and they have not fulfilled their promise. For example, the Affordable Care Act does not mandate coverage of all treatment options for drug addiction. Some health insurance plans graciously cover it, while others do not. Also, health insurance plans often require prior authorization, place limits on treatment duration, or require proof of failure using other treatments before covering the cost of medication-assisted treatment. More recent legislation, including the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), the 21st Century Cures Act, and the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act provided funding for grants, education, and clinician training, as well as increased access to treatment options.

These are welcome but insufficient advances. The epidemic has worsened despite recent legislation. Throwing money into a system fueled by profit is not a solution. A concerted and deliberate effort must be made to build interconnected institutions capable of providing comprehensive medical, psychological, and social support. Proper funding and adequate staffing with trained healthcare professionals and civil servants are also required. Moreover, solutions to the opioid crisis must address the social challenges faced by those struggling with addiction. Structural racism, white supremacy, and prejudice against rural Americans poison our institutions and our ability to enact better solutions.

Race and class

Media coverage of the opioid crisis highlights the interplay of race, class, and geography. Reminiscent of the racialized difference between crack and powder cocaine, contemporary media reports of the opioid crisis often distinguish between suburban and rural (read: white) and urban (read: Black and brown) drug use and addiction. White non-medical opioid users are often portrayed as victims (of “dirty” doctors and the pharmaceutical industry, or of anxieties surrounding deindustrialization), whereas Black and brown opioid users are portrayed as addicts. Cases of suburban and rural drug use highlight the spoiling of otherwise pristine communities, while examples of urban drug use demonstrate the inherent criminality of these communities. Motivations and social context are often explored in the former and not in the latter.

Class is also a factor in narratives of the opioid crisis. Descriptions of working-class drug use denigrate these communities. Poverty and dependence on “handouts” are linked to deficiencies in character, echoing narratives of the innate faults of urban drug users. Furthermore, white supremacy causes harm to poor rural white communities because it equates whiteness with affluence and innocence. The complex phenomenon of drug use and addiction in rural communities throughout Appalachia, for example, is simplified down to the use of “hillbilly heroin” that fuels crime and drug-seeking behavior.

Consequently, very different policy prescriptions are forwarded. Punitive measures tackle only one aspect of the crisis and are reactive rather than proactive. Mass incarceration for drug convictions, denial of meaningful employment, and lack of knowledge of treatment for substance use disorders reinforce the view that drug use, dependence, and addiction are individual problems. But the opioid crisis is not an example of individual moral failing. The ongoing opioid crisis demands not just a medical, but a social revolution in how we view, define, treat, and support those struggling with addiction.

Portugal’s success was multifaceted. It demonstrated the efficacy of multidisciplinary treatment focused on addressing individual medical needs together with social challenges. Combatting stigma against drug use and addiction also helped define Portugal’s public health measures. Cities and states here in the U.S. have begun this process, but more is needed.

The present COVID-19 pandemic only strengthens the need originally felt throughout the opioid crisis for universal health care. Solving drug use and addiction is difficult when individuals are burdened with navigating a disjointed, labyrinthine health-care system and extortionate insurance plans. Moreover, speaking of “access” to health care means little when communities have no hospital, clinic, or treatment facility nearby, and workers cannot take time off to seek or maintain treatment. Incentives are misaligned when employment is denied to those struggling with drug use and addiction, or treatment is shortened due to concerns of financial instability.

We need to struggle for a just, equitable, and empathetic health-care system. We must also fight against the purposeful starving of social safety net spending. Reliance on current institutions is inadequate. Judicial accountability, for example, is imperfect at best and not at all a deterrent of corporate greed. Lack of leadership and any semblance of compassion from the ruling class leaves workers the task of organizing themselves to implement systemic changes. We have the capacity to bring about radical transformation. The opioid crisis, like the COVID-19 pandemic, can be solved. In the face of bourgeois callousness, the working class can mobilize hope and a brighter future. Lenin’s words ring true, “Disunited, the workers are nothing. United, they are everything.”

A special thanks to the comrades of Virginia for their feedback and support.

Images: Pills, ajay_suresh (CC BY 2.0); Back pain, seoworkbuygenericpills (Pixabay); Methadone clinic, USDA, Flikr (public domain); Cocaine user, Marco Verch (CC BY 2.0).

Join Now

Join Now