The metaverse looms. With your latest headset and implants, there may be real stores, but the only ones you know are virtual, on Amazon. There may be real workplaces, but the only one you work in is a Microsoft Virtual Office. You may have real friends and co-workers, but you spend all day meeting and collaborating with their avatars in Facebook rooms and other locations. The majority of eyeballs in the world belong to Google. Your YouTube eyes see anything, and everything, in any dimension, and anywhere the IOT (Internet of Things) is active.

But let’s take off our headset. Remove the implants.

There is no doubt the virtual world is advancing as never before. The build-out of the Internet has transformed the sensible geography of the planet, and our lives.

Yet, the material footprint of the virtual world’s activity is immense. Massive data centers are distributed across the world. Satellites and fiber cables connect their hubs. Semiconductor manufacturing is one of the most capital and energy intensive of all industries. Biden’s Build Back Better plan promises huge subsidies to construct more computer chip factories in the United States. Vast wired and wireless networks connect billions of users and devices — all to ensure that things reach your front door in time to keep you from leaving home or office to travel to a box store.

The advancing social nature of both production and consumption of high tech confirms a long-standing forecast of Marx: the revolutions in production that capitalism incites lead toward increasing scale and socialization of production processes, which in turn have led to systematic antagonistic relations with private ownership throughout society. This contradiction is abundantly apparent in far-reaching political and social consequences when the chief corporate assets are profiles on half the world’s population, and the most valuable currency is information. The reforms of these corporations warrant more socialism than anti-trust action. Yet no reform is likely until the workers are organized, and the customers and other stakeholders too.

As tech leviathans go, Amazon is special. It combined a pioneering e-commerce software platform with a massive distribution system, allowing the goods we buy in the virtual world to quickly appear on our doorstep for real. Amazon’s commercial goal is to supplant, not just enhance, retail shopping. No malls are needed in the future. Amazon is the mall of malls, the Meta Mall, if you will.

Its profits are special, too. Amazon’s estimated revenue for 2021 is $457 billion, and its net earnings are $32 billion, an increase of over 1,000% since 2017.

Dealing in public goods

On top of Amazon’s material foundation arise many layers of software infrastructure on which apps of every description depend. Much of that software is licensed as “open or community sourced” software and considered “public goods” — no charge for use. The dirty little secret about open-source software is that its collaborative and shared information processes have been a better source of innovation and resilience than copyrighted software in many sectors.

“Public goods,” or “quasi-public goods” are defined in economics as a category broader than just taxpayer-funded projects. They include goods or services that are universally available and non-excludable (you can’t keep people from using it for free) and have no effective rivals. The lighthouse is a classic example. A lack of one or both characteristics makes a product — especially an intangible product — less suitable as a commodity. There are two practical reasons for this:

“Public goods,” or “quasi-public goods” are defined in economics as a category broader than just taxpayer-funded projects. They include goods or services that are universally available and non-excludable (you can’t keep people from using it for free) and have no effective rivals. The lighthouse is a classic example. A lack of one or both characteristics makes a product — especially an intangible product — less suitable as a commodity. There are two practical reasons for this:

1. As famously characterized by the economist Paul Samuelson, ideas are crappy stores of value. As commodities, intangibles “leak” (“depreciate” in economic terms) commercial value very quickly, often instantly. For example, an “owner” of an idea, like an algorithm, who wants to lease or sell its use must exclude its use from those who do not pay. This is necessary to preserve its exchange or tradeable “value.” This has proved impossible in the digital age. Despite a multitude of copyright and patent laws, intangibles can be easily copied. Indeed, the “owner” of an idea surrenders “value” to the public domain when they communicate it. Further, the owner usually fails to confess or acknowledge the diverse public sources of the idea. Ideas are never the product of a single brain. They are impossible not to share. Pharmaceuticals are especially guilty of claiming exclusive rights to a product, of which 99% of its composition and production technologies are in the public domain.

2. The difficulty of maintaining exclusivity strengthens the tendencies of rivals to merge. Stronger tendencies toward monopoly (or “market socialism,” as in China) emerge. In addition economies of scale tend toward global operations, and the selling of services and expertise rather than “products” are the chief economic consequences.

Intangibles, like open-source software, make better public goods than commodities. This “socialism” is eating the tech giants from the inside. A similar process is at work in the pharmaceutical industry.

The labor of millions of programmers and systems and network engineers is threaded throughout software code. Developers are no longer barred but incentivized to cross borders and corporate boundaries in pursuit of innovation. The greater collaboration made possible by the Internet has generated powerful, irreversible assaults on “proprietary ideas.” Microsoft buys Github, not to destroy it, as some expected, but to find ways to open source its own code, while gaining access to the “oceans” of talent whose projects and software storage are concentrated on Github. Microsoft is not alone. Most of the big software firms have moved from business models based primarily on licensed software to software services and rent-based models.

The point is this: Technology, and the advanced, objective socialization of both virtual and material production, are blurring the lines between public and private goods. The virtual worlds of the giant tech companies are riding on vast software, hardware, and global production/distribution systems, most of which are public goods, services, and infrastructure. The reverse is also true. Public welfare is critically reliant on the performance of too-big-to-fail private firms, whose downfall would bring catastrophic consequences.

The true gold — user profiles

Then there is the true gold, and the source — beyond wealth — of the immense social and political power of the high-tech firms: user profiles.

Profiles are built from the tracks every user leaves behind in every interaction — clicks, “likes,” posts, and reposts — they have on the tech platforms while reading emails, chatting, watching videos, or making purchases. For Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Apple, the profiles number in the billions — more than half the population of the planet. It becomes hard to imagine what “privacy” will come to mean. It’s even deeper than that. As the Internet of Things (IOT) grows, broadly deployed sensors record and broadcast multi-dimensional data to Amazon and other clients. The clients may themselves be robotic, drones, or other instrumentation, including cloud-based artificial intelligence (AI) optimization programs. Such programs manage work shifts, temporary workforce needs, and supply chain shocks across the company’s physical and virtual networks, in order to minimize delivery failures — an existential feature of Amazon’s takeover of retail.

It’s even deeper than that. As the Internet of Things (IOT) grows, broadly deployed sensors record and broadcast multi-dimensional data to Amazon and other clients. The clients may themselves be robotic, drones, or other instrumentation, including cloud-based artificial intelligence (AI) optimization programs. Such programs manage work shifts, temporary workforce needs, and supply chain shocks across the company’s physical and virtual networks, in order to minimize delivery failures — an existential feature of Amazon’s takeover of retail.

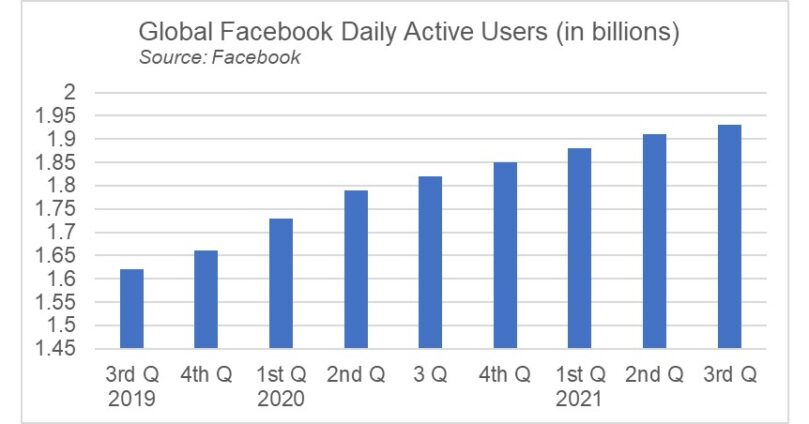

One may ask, “Optimize what?” The answer is simple for the big tech companies: whatever keeps the traffic, the hits, the commerce, the profiles, and profits growing.

The amassing of user profiles benefits not only the tech companies. The current controversies over the role of social media in the Trump/fascist phenomenon, and later the fascist insurrection, have shown that user profiles also have political “value” and power. Which, of course, translates into even more profits for big tech.

But what is the value of profiles as a commodity? They help maximize demand. But they are not taxed. They do not show up on the corporate balance sheet. Who owns them? No matter how that question is resolved, if it can be, the big tech companies “possess” the profiles, and “possession is nine-tenths of the law,” according to most lawyers I have known.

The corporation that understands the distribution of interests and power in a nation better than a government will dominate that “government.” Therein lies the kernel of the basic question driving the necessity of reform. If a democratic state does not exercise “information” rights superior to that of a single private interest, then the democracy will fail. If there is to be a censor of political speech, for example, Facebook will decide the matter if the state does not. It is an unwelcome choice to most Americans, no doubt, who treasure “free speech.” Who imagined that the Wild West of the 1990s Internet would be consumed by leviathans?

The calls for reform of the too-big-to-fail components of these firms are growing louder. Perhaps they will lead to anti-trust initiatives. That would be the traditional bourgeois, liberal approach. Unfortunately, the natural centralization-socialization tendencies in high tech will likely prevail. That leaves public — government — stakeholders and/or powerful regulatory leverage as the only alternative for democracy, an option that is barely conceivable, given the current political climate. However, there is a potential, indispensable mediating force inside these firms — an organized and empowered workforce.

The workforce

Skilled trades and engineering

A sizable minority of employees are some of the most talented developers and engineers in the country. These folks are generally being paid above median income, often into six figures, for their work. However, the mission of the enterprise is a key motivator in the programming trades. Betrayal of the skilled and technical trades’ commitment to a company’s mission, as is being reported in Amazon, is very bad for a corporation whose most valuable capital input is the human being, a value multiplied by high morale.

Thus there are significant interests and motivational benefits in aligning labor organizing campaigns with the features of the company’s mission that do serve the public interest, improve people’s lives, and help connect, not divide, the peoples of the world.

Warehouse workers

The number of fulfillment centers may exceed 400 in the U.S. alone, with at least 40 new ones under construction. These centers, many located in remote areas, employ just shy of 1 million U.S. employees in hard, dangerous, volatile, and underpaid work. The current starting rate of $17.50 in many locations is enough to pay rent, but not buy a house or send a child to college. Jeff Bezos rides safely to the heavens while his fulfillment workers get injured at rates that are double the national average for warehousing occupations. This is the thanks they get for their services as essential workers in the pandemic.

Unlike most other industrial or warehouse workplaces, the fulfillment centers combine the pressures of advanced, large-scale automation; large workforces; and volatile workflows and loads. Adding to the volatility are the recent pandemic-related increase in global demand and stresses on the supply chain.

A big investor in AI and robotics, Amazon uses AI to set work schedules, hire and fire employees, and track employees’ productivity, including their “time off task.” AI also helps optimize much of the fulfillment automation. A result is that many workers’ principal partners are instrumentation controls — robotics.

The fast pace of work, low pay, and poor working conditions drive high turnover for new employees, whether through firings, lay-offs, or workers quitting the job. The employee turnover rate is so high — over double that of the average of retail and warehousing industries — that Amazon bosses are reportedly worried about running out of new hires.

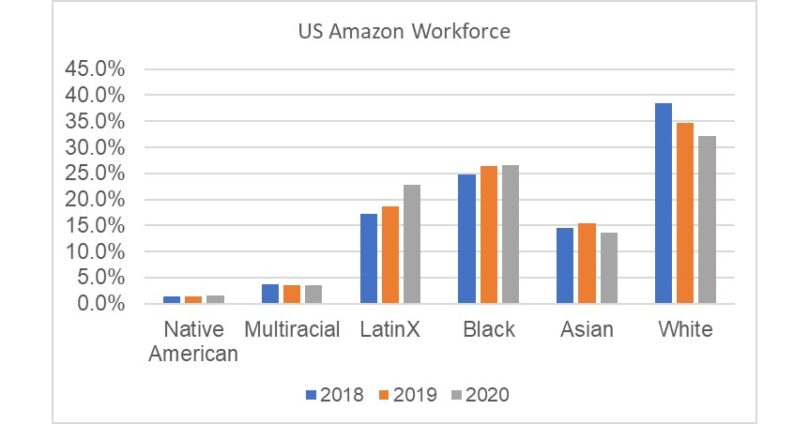

There is now a migrant Amazon workforce working the waves of overages and shortages across fulfillment centers, as featured in the opening of the streaming series Nomadland based on Jessica Bruder’s book by the same name. Amazon started its CamperForce work program in 2008 to exploit itinerant workers traveling around the country while living out of their RVs, many of them elderly or experiencing homelessness. Accelerating since the pandemic, this trend constrains local schools, health services, addiction centers, and the criminal justice system in ways that are yet unknown. The Amazon workforce has the virtue of resembling the overall US workforce in composition, and it has become more diverse over the years. This has a virtuous consequence: it will compel union organizing campaigns to deeply embrace equality and justice for African Americans and other people of color, people of all ethnicities, the LGBTQ community, and women. This will be important, since the chief weapon of corporate anti-union resistance is the exploitation of racial, ethnic, and gender divisions.

The Amazon workforce has the virtue of resembling the overall US workforce in composition, and it has become more diverse over the years. This has a virtuous consequence: it will compel union organizing campaigns to deeply embrace equality and justice for African Americans and other people of color, people of all ethnicities, the LGBTQ community, and women. This will be important, since the chief weapon of corporate anti-union resistance is the exploitation of racial, ethnic, and gender divisions.

Who are Amazon’s stakeholders?

Amazon further stands out in the number and complexity of its stakeholders — beyond stockholders or employees — impacted by its business.

The 10 million third-party sellers on Amazon are a global constituency. From book publishers to piano dealers, their primary concerns are product placement and the percentage of a sale that gets returned to them. There are few alternative platforms for sellers of goods, so they are compelled to take the cut Amazon offers. For the privilege of selling their products on Amazon’s Marketplace platform, sellers pay about 34% of their revenue, according to a recent study. One can imagine Jeff Bezos threatening these sellers: “Make me grow. Or I will leave you for someone who will.” Employees and dependent businesses thus have a common interest in ensuring standing sufficient to bargain for equity.

The 200 million Prime members (a fraction of Amazon’s customer base) consume the biggest share of U.S. media services and delivery services. They also generate the most retail sales on the Internet. The ideological and cultural impact of Amazon’s media footprint is not trivial, considering the company’s dominant market power.

Other stakeholders are the over 1 million subscribers and users of Amazon Web Services, which now hosts the largest U.S. cloud computing platform and hosting service. And 100,000 of these clients are large corporations or organizations. Amazon’s new CEO, Andy Jassy, comes from this division — where Bezos sees the future. Since there is no practical way to count the value added by all those accounts, their market valuation is probably underestimated by an exponential magnitude.

The most grassroots of the stakeholders in Amazon are the communities where the fulfillment centers are located. Tax abatements, utilities, land and road use, and other benefits can open the doors to positive economic development or doom a community to ruin, depending largely on local and state politics. Consider the financial impact on education, health care, security, and the environment of an enterprise with 800 truck bays running 24/7, alternating between two and six thousand workers. Will a tax abatement be offset by additional revenue from a bigger employee tax base? These issues provide the keys to establishing unity between Amazon workers and community alliances and interests.

Finally, there’s the U.S. postal service, also affected by Amazon. It must absorb overages — loads that exceed Amazon’s internal or contracted delivery services (UPS, etc.) — while remaining understaffed and underfunded.

The labor movement

The labor movement is recognizing the centrality of organizing Amazon, and the opportunities that the contradictions in its workforce dynamics expose.

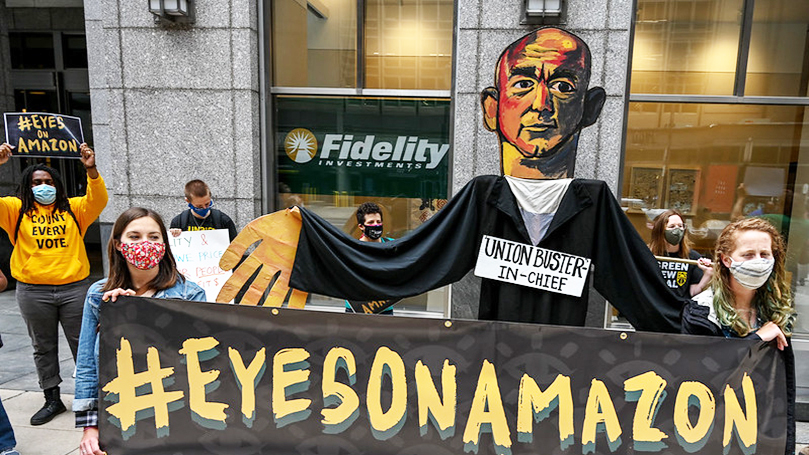

The RDSWU held a breakout election in Bessemer, Alabama. It exposed the anti-union animus of Amazon leadership, which unleashed a barrage of illegal, dishonest tactics. As a result, the union lost the NLRB election but proved that the foundations of significant union organization were strong. The Biden-led labor board has since charged Amazon with unfair labor practices and ordered a new election.

The Teamsters have declared a national organizing campaign, pledging significant resources. In an independent effort, the Amazon Labor Union has also filed an NLRB election petition in Staten Island, New York. In addition, there are at least two serious rank-and-file efforts underway within Amazon.

Active unionization campaigns are an essential part of reform. Uniting them is an important contribution of communists and socialists. However, it will take more than unionism to win bargaining rights. All the stakeholders, including the president of the United States, will need to be involved.

The campaign to reform Amazon is not an anti-Amazon campaign. No one can detract from Amazon’s historic transformations in virtualization and its ability to connect consumers, workers, services, and creations from around the world. Amazon is a creation of millions of people, upon which millions rely, but currently in the control of a trillionaire. A genuinely Marxist point of view — as I read Marx — might put that differently: A trillion dollars of capital is a material social force in its own right.

Linking the many workers, stakeholders, and constituencies with a common vision of empowerment and strengthening the public’s interest in Amazon is a righteous program aimed directly at alleviating the scourge of unjust divisions of wealth and the loss of real rights. It is a struggle that can midwife the restructuring of capitalism itself — subordinating it to more public direction.

How can you help?

1. Join the Communist Party’s campaign to bring reforms and worker empowerment to Amazon and other too-big-to-fail firms. Contact laborcommission@cpusa.org to get involved.

2. Bring together the many constituencies and empowerment efforts through the labor and people’s press, including the People’s World. Through honest and truthful class-conscious storytelling, we can create an authentic record of workers’ struggles for empowerment through both unionization and political activity.

3. Work collectively and learn the tactics of workplace and related community engagement.

We do not have to invent much. We will learn much from the workers. When our unity efforts spark a flame, all the Amazon workforce needs to do is sneeze together, and the temples on Wall Street will tremble.

Images: Amazon protest, Joe Piette (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Lighthouse, Rodney Campbell (CC BY 2.0); FB daily users, chart design (CPUSA), source: Facebook 3rd quarter earnings report; US Amazon workforce demographics, chart design (CPUSA), source: Amazon; RWDSU banner (Facebook).

Join Now

Join Now