It is always risky to construct an organic whole, a single all-inclusive meaning or, more boldly, a single metaphor for an entire book. But a larger definition leaps out at me. First, and most important, Five Days, Five Nights succeeds and does so beautifully, giving us exactly what the author intended — an almost perfect piece of fiction. I say “almost” not because I found fault, but because I am certain the author would use that word. Authors are always self-critical, even of that which they would consider completed.

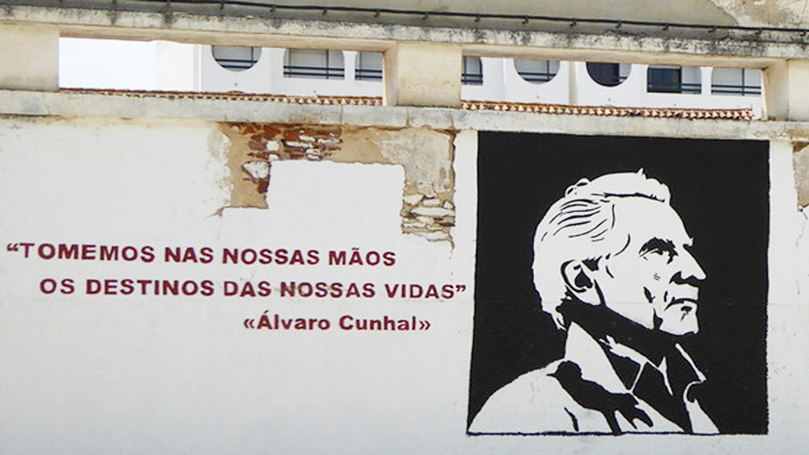

I loved Five Days, Five Nights by Manuel Tiago, known to his Portuguese Communist companheiros as Álvaro Cunhal, long-time leader of the Portuguese Communist Party. I hung on every word. Indeed, on almost every page there was a cliff for just that purpose!

Cunhal wrote Five Days during an 11-year imprisonment in Forte de Peniche, from which he heroically escaped on January 3, 1960. He took with him a longer manuscript titled Até Amanhã, Camaradas (Until Tomorrow, Comrades) but left behind Five Days. When fascism ended in Portugal, the manuscript was returned to him, and he published it in 1975 under the pseudonym Manuel Tiago. The plot is described in People’s World:

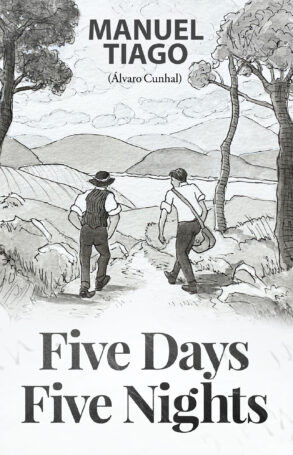

Five Days, Five Nights is the fictional story of 19-year-old André and his attempt to flee to Spain from oppression in Portugal. To cross the border he enlists the help of the shady, dangerous, older criminal Lambaça. They must cross the rough border terrain, passing through villages and encountering a few peasants along their way.

I have to offer praise for the seamless translation by Eric A. Gordon, for it is hard to tell where where the Portuguese leaves off and the English begins, which may be the very definition of any really successful translation.

Five Days, Five Nights was a joy to read, and in a single reading at that (with a short lunch break). I see this work as a single subtle and well-crafted metaphor, political, yes, but much more. The words “poetic” and “poignant” come to mind.

The exact spot where I felt the story to be not just political, but comradely communistic, was in chapter 13 when the two main characters, Lambaça and André, take their leave of Zulmira, a beautiful country girl with whom they overnighted, who picks up a little extra money “working”: “The girl then said goodbye with her hand, in a gesture so sad and forlorn, that he would never stop thinking about it, nor ever stop feeling its pain.” (The edition issued by International Publishers also includes illustrations by Ilse Gordon, who lovingly captured this particular moment.)

The tale is, I believe, a metaphor for revolution. I see, in both plot and the personality of each character, that which is part of all revolutions. One quality common to revolutions, uncertainty, runs through the story. André cannot tell us exactly why he is on this journey or what his final destination will be. Also, he is young, as are all revolutions, hence the great degree of uncertainty, with much room for the maturation to come. Zulmira symbolizes the sadness of the oppression that must be overcome. And Lambaça holds within him both the nobility and the sometimes oppressive nature of revolution. We cringe at times at his gratuitous harshness and human flaws, but these are part of all revolutionaries. Please enlighten me, someone, if history has yet recorded a perfect revolution.

The tale is, I believe, a metaphor for revolution. I see, in both plot and the personality of each character, that which is part of all revolutions. One quality common to revolutions, uncertainty, runs through the story. André cannot tell us exactly why he is on this journey or what his final destination will be. Also, he is young, as are all revolutions, hence the great degree of uncertainty, with much room for the maturation to come. Zulmira symbolizes the sadness of the oppression that must be overcome. And Lambaça holds within him both the nobility and the sometimes oppressive nature of revolution. We cringe at times at his gratuitous harshness and human flaws, but these are part of all revolutionaries. Please enlighten me, someone, if history has yet recorded a perfect revolution.

The novella ends with André about to enter a new country and a new life. We hope to meet him again and learn more about both him and revolution. And we will, because this is only Manuel Tiago’s, or Álvaro Cunhal’s, first novel to appear in English. A series of “Manuel Tiago” novels and stories are forthcoming from International Publishers, and we will meet many other characters who, like Lambaça and André, will pursue in their own ways the goal of overturning Portuguese fascism.

As a reader and lifelong political activist (I turned 90 this year!), I have to wonder why a man of such prominence in the Portuguese resistance would spend so much of his time writing fiction, but if Five Days, Five Nights is but the first sample of his writing accessible to English readers, with much more to come, I think I understand why.

Thanks to the efforts of the translator, I now not only have a new book but have met a new author, friend, and comrade. So may we all — that is my fervent hope.

A People’s World interview with the translator, Eric Gordon, can be read here.

Five Days, Five Nights

by Manuel Tiago (Álvaro Cunhal)

New York: International Publishers, 2020

Image: cyclingshepherd (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Related Articles

- Women’s History Month Book Talk: Lessons from Revolutionary Organizing

- Erasing History: A useful, if liberal intro to fascist revisionism

- Trailer Park America highlights the crimes of capitalist housing

- From our readers: the best of 2023

- Come celebrate International Publishers’ centennial anniversary!

Join Now

Join Now