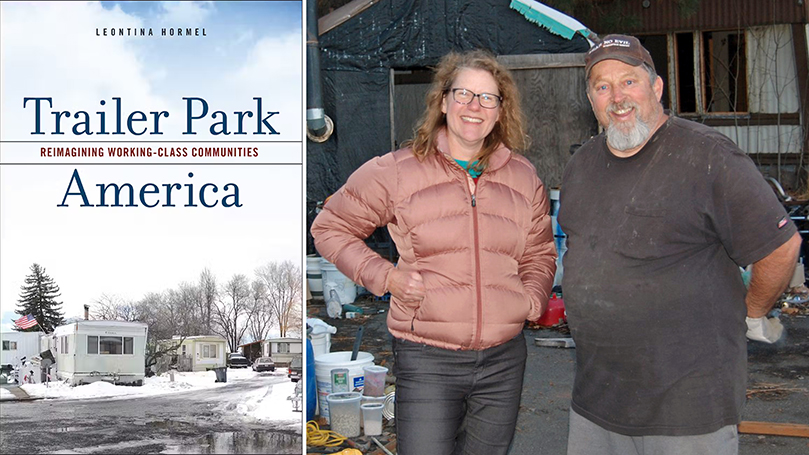

Sociologist Leontina Hormel’s Trailer Park America is a granular examination of an ill-fated rural, working class community in a mobile home park located a few miles outside the small town of Moscow, Idaho.

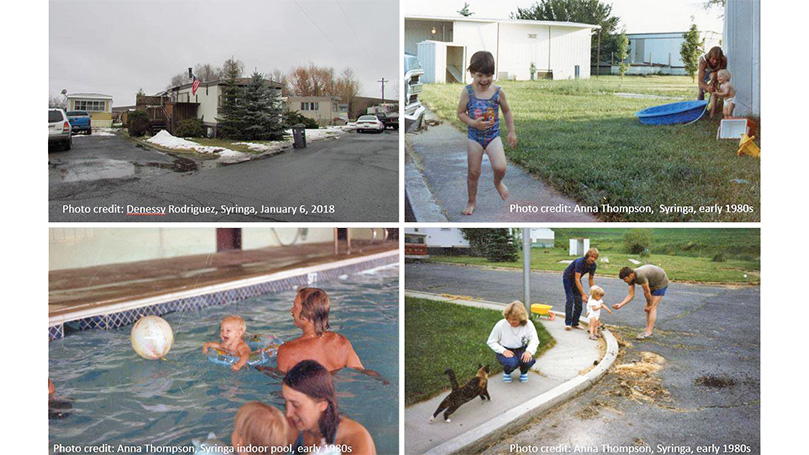

Syringa Mobile Home Park was established in 1966 and for a generation offered an affordable housing option for “half-way homeowners,” who bought their manufactured homes and rented land in the private park. Young families, retirees, veterans, disability recipients, and graduate students at the nearby University of Idaho made their homes here.

Through the late 1970s, Syringa was known for its “resort-like atmosphere,” its recreation center with an indoor pool for residents, and its tranquil setting with spectacular mountain views. It was a thriving working-class community — until a giardia outbreak (a parasite that causes a diarrheal disease known as giardiasis) in 1992 indicated serious problems with the water and sewage system that had served the park for almost thirty years, and then caused its ultimate closure.

Syringa was not unique. Trailer home parks were booming in the 1950s and ’60s, the result of a confluence of various factors: the need for affordable housing for returning soldiers, policies like the G.I. Bill and favorable FHA loan terms, and an adaptation to peacetime demands for maintaining the manufacturing capacity that had been ramped up for the defense industry during World War II. It was less costly to build these parks in rural areas, where regulations were relaxed and government oversight was minimal. Instead of pricier connections to city water, rural parks could depend on wells and sewage lagoons built on private land.

The inadequacy of the water and sewage system in Syringa was not accidental. It was a result of the choices the builders made, the ignoring of early warnings, and the deferral of maintenance by unscrupulous park owners. Beginning with the giardia outbreak, the park’s residents suffered periodic breakdowns in the water and sewage systems. Untreated water from sewage lagoons contaminated the nearby river and compromised residents’ drinking water. The park’s absentee landlord, a lawyer living a six-hour drive away, deferred needed maintenance and took steps that actually caused further damage to the infrastructure. Water was sometimes shut off without notice, and a boil order was in place for months. At one point, residents went without clean water for 93 days.

The landlord was sued three times: a class action lawsuit on behalf of residents, a water systems lawsuit filed by the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, and a Clean Water Act complaint filed by the Idaho Conservation League. The landlord was found liable in all three cases. When he continued to fail to make necessary repairs, the county responded by condemning some homes, by “red-tagging” them, making their occupancy illegal and forcing some people from their homes. The red tags were supposed to pressure the landlord into making repairs, but they only hurt the residents. When the closure was announced, 38 households remained. These “Syringa refugees” suffered stigmatization as “trailer trash.” Their landlord had neglected the park, but the residents paid the price.

The settlements that residents received from the court cases were paltry and did not begin to cover relocation expenses, much less the money they had invested into their homes over the years, while faithfully paying rent for the land. They were cheated by their landlord, who declared bankruptcy and landed on his feet. Residents were also let down by county officials, who should have been protecting residents, but ended up serving the landlord. When residents needed assistance relocating, the county washed its hands of the problem, viewing it as the demise of a “private business,” and therefore not the county’s concern. The residents were failed by the local press, which used the park’s problems against the residents themselves by spreading “trailer trash” stereotypes and fomenting community-level prejudice. One resident described the experience as a“scorning down” against the community. County officials and others who could have helped residents resorted to the stereotypes to justify not taking action.

Throughout the book’s chapters, Hormel shows how rural working-class people are immiserated by the structures of capitalism, particularly global “campaigns of privatization and deregulation.”1

A unifying theme throughout the book contrasts two perspectives: housing as a commodity and housing as a human right. When housing is commodified, property rights take precedence over human needs. Everywhere, “distorted markets … favor luxury, rather than affordable, housing.”2 Consolidation of finance capital has enabled private equity firms and real estate investment trusts to buy up housing by out-competing low-income, working-class households. When housing options shrink, rates of unhoused people skyrocket while landlords profit from scarcity. These global ramifications of commodified housing are exacerbated by the decreasing purchasing power of the working class and the rise in costs for basic needs. Hormel describes one trend as the “feminization of labor.” With the decline in manufacturing, men’s labor has become more like women’s labor has always been: low-wage, part-time, temporary, and insecure.

Housing as a human right recognizes that households with continuous, secure housing have better life chances in health, employment, education, and social networks. Capitalist societies have sometimes created limited social housing through measures like the G.I. Bill — although the beneficiaries of this were mostly white men — and nationwide versions of rent control that were passed in 1939 and in 1970.

The good years that Syringa had until its original owner sold the park in 1976 gave residents the opportunity to create networks of care, in which much of the unpaid labor on which capitalism depends takes place. Hormel introduces the concept of the “reproductive commons,” where “seemingly ‘free’ services” — such as caring for the elderly and children in the neighborhood, or helping each other out by cooking or sharing food — offer the mutual benefits of community life. Capitalism depends on these activities, but doesn’t pay for them. When the Park closed, the residents of Syringa Mobile Home Park lost their reproductive commons, along with their homes.

In one early chapter, Hormel situates Syringa in the broad sweep of natural and human history. The area is called the Palouse and is a prairie ecosystem known for its rich loessial soil. Indigenous peoples settled in the region an estimated 16,000 years ago. For centuries, the region was home to the Nimíipuu tribe, a hunting and gathering people who regularly returned to the Palouse to dig for camas root, a plant whose tubers made up half of the annual diet of the people. Europeans first arrived in 1805, and in the land-grab that followed, enclosed the “commons” where the Nimíipuu gathered and hunted. They destroyed the camas fields and established practices that led to a “near-complete ecocide and, consequently, erasure of Indigenous lifeways and culture.” In short, it amounted to a “cultural genocide,” Hormel writes.3 The contrast between the centuries of indigenous land use with decades of ecosystem destruction indirectly illustrates Marx’s analysis of capitalism’s “metabolic rift.”

The richness of detail about the experiences of specific residents over the last years of Syringa serves to humanize abstract processes taking place on the national and global level. The reader gets to know the stories of some of the residents, including those who remained when the park closed. Some of those who remained had severe needs and suffered from extreme poverty. As it reached closure, the park environment was described as “a physical expression of insecurity and humiliation,”4 constituting a “zone of discard”5 that reflected the feelings of the residents, as well as the state of the park.

Finally, a word about methods of research, which in Hormel’s case were thoughtful, thorough, and systematic. She participated in park life over the course of its final decade, studied legal documents and newspaper articles, conducted a comprehensive study of housing trends in Idaho and in the United States, and did collaborative research with Nimíipuu environmental activists. She approached her work with the residents of Syringa with profound respect and humility, conscious of her advantages as a university professor and willing to use those advantages deliberately in their service.

The stated purpose of the book is to be “an inspiration and a tool for community advocacy”6 and Hormel’s courage to use her work to support the residents of Syringa is clearly visible. She worked with them to help research resident-ownership options (made impossible by circumstances in Syringa’s case), connected them with pro-bono legal assistance, lobbied for a better response from elected officials and bureaucrats, and assisted with public events staged by the residents to counter the stigma they endured.

Housing insecurity is one of the most serious crimes of capitalism in our time. Hundreds of thousands of unhoused people, skyrocketing rents and eviction rates, and lack of community networks are some of the results of treating housing as a commodity instead of a human right. This timely and informative new book offers both a very close examination and a broad overview of the consequences of capitalist housing policies.

1. Leontina Hormel, Trailer Park America: Reimagining Working-Class Communities, (Rutgers University Press, 2023), 81. ↩

2. Ibid., 16. ↩

3. Ibid., 43 ↩

4. Ibid., 215 ↩

5. Ibid., 220 ↩

6. Ibid., 11 ↩

Images: Trailer Park America book cover (from Rutgers University Press) / Author with Syringa resident by Chris Norden via Leontina Hormel (Facebook); Photo collage: Syringa over the years by Denessy Rodriguez, Anna Thompson via Leontina Hormel (Facebook); Home in Syringa Mobile Home Park three weeks before park closure by Dawn Trottier via Leontina Hormel (Facebook); Visiting with a remaining resident by Leontina Hormel (Facebook); View from Syringa by Leontina Hormel (Facebook); Meeting with mobile home community residents by Leontina Hormel (Facebook)

Join Now

Join Now