This article on Doxey Wilkerson is the first in a series on Communist educators brought to you by the CPUSA Labor Commission Educators Subcommittee. Stay tuned for more.

“Our most effective teachers are those who … are at war with bourgeois ideological distortions and illusions.” – Doxey Wilkerson

Struggles in education — led by teachers, students, and community members — are key forces for democracy. The impact of one teacher can reverberate throughout nations and generations. A teacher that had such an impact was Doxey Wilkerson.

Born in 1905, in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, Doxey learned about the importance of political struggle at a young age. Living under the yoke of Jim Crow, and the realities of working class life profoundly impacted him. “The experiences of my childhood and adolescence did much to shape the attitudes of social protest which later became driving forces in my life,” he would later write in a 1943 edition of New Masses.

Wilkerson’s mother held three jobs in order to make ends meet. Meanwhile, Doxey excelled academically while living in a deeply unequal society. This contrast led him to reflect that “it just did not seem fair” that his mother had to work so hard to have so little.

At age 14, Wilkerson spent his summer working ten-hour shifts operating the receiving end of a ripsaw at the Forrester Nase box factory. “I still recall how the factory wheels continue to buzz in my head for hours after I return home.” He identified as a part of the working class and developed “a hatred for exploiters.” These early working experiences informed his analysis of the interconnected realities of racial and class politics in the United States.

Doxey attended Kansas City public schools where he developed a passion for playing the clarinet. Although he was admitted to the University of Kansas, segregationist policies barred his participation in the collegiate band and many other activities. Instead, he pursued English and joined the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, which focused on building up African American men.

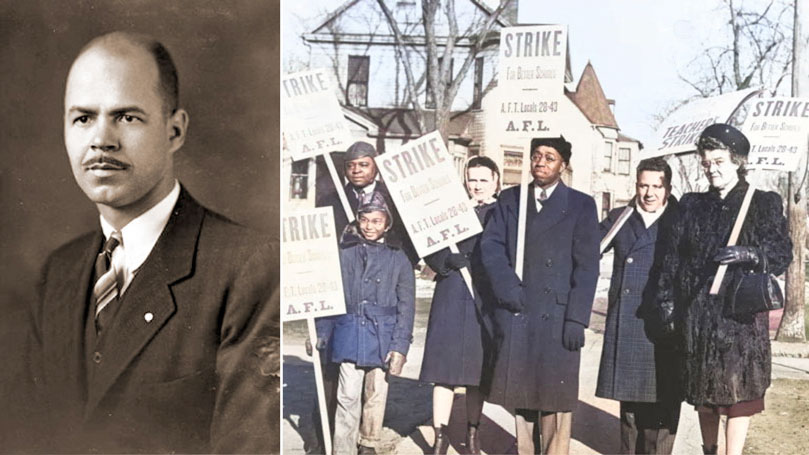

Upon graduating with a bachelor’s and master’s degree from the University of Kansas, he became an assistant professor at Virginia State. During his tenure at the college from 1929 to 1935, he helped organize local teachers and Black voters to increase political participation. Subsequently, the state labeled him a “bad Negro.”

Soon after, he departed to Howard University where he found a much more welcoming environment to fight for equality. At Howard, he helped organize the faculty into a union and regularly fought against segregation policies and police brutality.

Simultaneously, Wilkerson served as Vice President of the AFT from 1937–41. He pushed the union to move beyond professional concerns and take bolder stances on racial and economic issues.

Furthermore, he joined the Roosevelt administration, earning an appointment to the Advisory Committee on Education, established to evaluate and recommend improvements to federal education policy during the Great Depression. As a part of this group, he authored the 1939 report Special Problems of Negro Education.

In 1942, Wilkerson became vice president of the International Labor Defense (ILD), a legal advocacy organization which defended political prisoners and Black Americans falsely accused of crimes. Most notably, the ILD championed the innocence of the Scottsboro boys as an international issue.

Also in 1942, Wilkerson was appointed to the Federal Office of Price Administration (OPA), a New Deal agency responsible for controlling prices and preventing inflation during World War II. Within this position, he travelled across the South helping African American schools develop programs focused on wartime consumer education. Witnessing the exploitation of white workers, and the superexploitation of Black workers across the South, which he understood as interconnected problems, Wilkerson was not content to hide his Marxism within this role; he made it known.

CPUSA

In 1943, Wilkerson resigned from the OPA and left his teaching role at Howard University, announcing his membership in the Communist Party USA. “I joined the Communist Party as the logical and impelling next step in a series of experiences which pointed inexorably toward that end,” he wrote.

“My feelings as a Negro American, considerable study of social theory, direct observation of social relationships in many parts of the country, increasingly extensive activities in the trade union movement, and in numerous progressive organizations, all served to define social values and to develop social insights, the inevitable outcome of which, at some time, simply had to be affiliated with the Communist Party.”

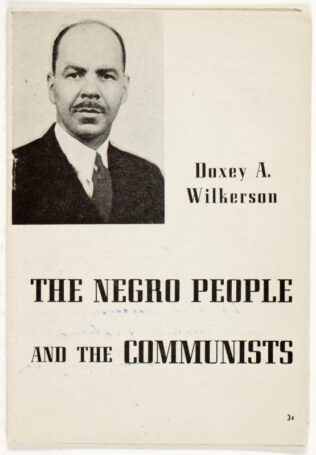

That same year, Wilkerson also wrote the pamphlet “The Negro People and the Communists,” in which he stated that “Communists have always understood this need for Negro–white unity better than any other group in society.”

The Jefferson School educator

His most significant impact was seen through his teaching in the Jefferson school of social science, as well as his tenure as director of curriculum from 1948–56. The Jefferson school was part of a broader network of Communist Party schools, including the Tom Paine school in Philadelphia, the Abraham Lincoln school in Chicago, the California Labor school in San Francisco and the Samuel Adams school in Boston. The purpose of these schools was to train working-class students in Communist thought and to mobilize them into organizing.

His most significant impact was seen through his teaching in the Jefferson school of social science, as well as his tenure as director of curriculum from 1948–56. The Jefferson school was part of a broader network of Communist Party schools, including the Tom Paine school in Philadelphia, the Abraham Lincoln school in Chicago, the California Labor school in San Francisco and the Samuel Adams school in Boston. The purpose of these schools was to train working-class students in Communist thought and to mobilize them into organizing.

While teaching at the Jefferson School, Wilkerson made clear that it was not a pursuit of knowledge as a neutral or purely academic exercise. Instead, he embraced a tradition of critical pedagogy and social reconstructionism, believing that meaningful education should prepare members to actively work toward building a more equal society. The school’s courses were specifically geared toward building organizing capacity:

“As a result of studying in any course at the Jefferson School, a student should be able more effectively to influence his associates in the shop and community. He should be a better worker and leader in his trade union, youth, political, negro or other people’s organizations. He should be a better election campaigner, a better fighter for Trade union unity and labor political action, a better organizer of negro-rights struggles, a better fighter for working-class values in literature and art. He should be able to play a more effective role in struggles to combat the effects of depression, to improve housing, to defeat McCarthyism, to win amnesty for victims of political persecution, and to impose peace on our war-bound imperialist government.”

Wilkerson explicitly named them as peddling “capitalist propaganda.” NAM opposed the New Deal and pushed anti union propaganda in the workplace. They vociferously attacked and prevented progressive history textbooks from entering schools.

In public education, radical teachers were being purged from the NYC teachers’ union. Due to the Timone Resolution, it was no longer allowed to function as a collective bargaining representative for NYC public school teachers; it was barred from handling faculty grievances or holding meetings within public school buildings.

In the face of all of this, the Jefferson school ultimately closed. The school was decreasing in membership in the early 50’s due to the Red Scare and infiltration by the FBI. Members explained that, “Unwarranted persecution by the Federal Government created a financial situation in which it is impossible for the school to continue.”

Although Wilkerson left the Communist Party in 1957, he remained steadfast as an educator and civil rights advocate. In September 1959, he accepted a teaching position at Bishop College in Marshall, Texas. However, by March 1960, he was pushed to resign after he helped organize student protests against segregation at Woolworth lunch counters.

Doxey Wilkerson refused to feign neutrality in the face of reactionary forces. Through his life, he showed that education is one of the most critical terrains of political struggle, dedicating his life to organizing and agitating for people’s movements to achieve racial and class liberation.

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Images: Doxey Wilkerson c. 1940 (blackpast.org) / The American Federation of Teachers (AFT), Locals 28 and 43 strike in 1946 (phillys7thward.org). Wilkerson had been Vice President of the AFT from 1937–41, helping to push the union into fighting for broader racial and economic justice; Doxey Wilkerson (second from the right) with Town Hall of the Air program moderator George V. Denny, Howard University President Mordecai Johnson, and Howard’s law school acting dean Leon Ransom in 1942 (Washington Area Spark / Flickr); pamphlet by Doxey Wilkerson (Amsterdam News)

Join Now

Join Now