“There are deaths which make one immortal”

— Tran Dinh Van, The Way He Lived: The Story of Nguyen Van Troi

Anyone who doubts the murderous nature of American capitalism need only glance at the war in Vietnam. Between 1964 and 1973 America dropped eight bombs per minute on peasants, women, and children — more tonnage than used in all of World War II (Turse, p. 197). Vietnam was used as a laboratory for testing fiendish and cruel U.S. weaponry, “perversions” such as flechette pellets and white phosphorous (Boston Lesbian Feminists, 154).

America even resorted to herbicidal warfare, targeting “not specific weeds but entire ecosystems” so that in Vietnam “the forest was the weed” (Zierler, 2). Approximately five million acres of forests were defoliated with 20 million total gallons of the carcinogen Agent Orange in an attempt to expose communist guerrilla fighters. Scientists labeled this type of warfare “ecocide” (2). It was an assault, not just on a people, but on the sacred earth and water that sustain them. The suffering continues to unfold today in cancers and birth defects.

Journalist I. F. Stone predicted that “there is a possibility that Nixon would finally use nuclear weapons to blow Vietnam to bits . . . genocide of a whole people in order to save male face” (Boston Lesbian Feminists, 156). He was right. Years later word leaked that U.S. leaders “had been seriously and secretly contemplating a fierce escalation of the war, possibly to include the use of nuclear weapons. Persistent and aggressive antiwar sentiment . . . made it politically impossible . . . so the Sixties antiwar movement had no way to know how great was their success, how real was their achievement” (Zaroulis & Sullivan, 296).

“Death and destruction that stuns the imagination”

A distinguished International War Crimes Tribunal, just like the panel that sat in judgment of Nazis at Nuremberg, was convened in 1967 by philosopher Bertrand Russell. The Russell Tribunal found America guilty of war crimes and genocide in Vietnam. Comments by Tribunal members include “I sat numbed by the horrors,” “death and destruction that stuns the imagination and legitimizes — nay requires — use of the term genocide,” and “I doubt if Americans will ever be able to comprehend the depravity . . . or the nightmare of Vietnamese suffering and U.S. contempt for Asian life” (Albert and Albert, 335). Yet Vietnam emerged as a historical bright spot because, just as at the Little Big Horn, the good guys finally won. Famed historian Howard Zinn wrote that the war was “modern technology versus organized human beings and the human beings won” (Zinn, 460).

Are there ghosts from that war, human beings who died needlessly and unjustly but heroically, knowing that their cause was just, now wandering about, still seeking to be heard?

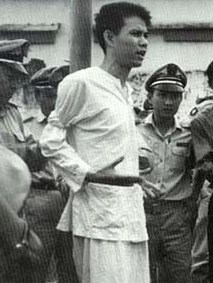

In 1964 Nguyen Van Troi was a very young Vietnamese electrician from the village of Quang Nam. He was also a communist patriot and member of the National Liberation Front. Trỗi had been married to Thi Quyen Phan only 19 days when he was arrested by South Vietnamese puppet regime troops for attempting to assassinate Robert Strange McNamara.

McNamara was a primary architect of the Vietnam war, serving as U.S. Secretary of Defense under two presidents, Kennedy and Johnson. As a former president of Ford Motor Company, he was part of what sociologist C. Wright Mills called the “power elite” made up of three institutions: the military, political leaders, and the corporate rich (Menand, 49).

McNamara, as creator of the ghoulish and dispassionate body count, was a statistician and reductionist, quantifying death by tallying dead Vietnamese bodies as a measure of U.S. success. But in a breathtaking admission many years later, he acknowledged, “We were wrong, terribly wrong” (Steinbach, 3). He revealed true ruling-class arrogance by confessing that he and his fellow elite military and political criminals had launched and led a war that killed millions yet “had not truly investigated” the wisdom of that war and Vietnam’s long history as a warrior culture, resolute and successful for centuries in resisting foreign invaders (15).

Troi’s young widow Quyen said, “My husband was a liberation fighter in a secret commando unit operating in Saigon . . . he was given the task of killing McNamara by planting a bomb under the Cong Ly Bridge” (Van, 63). It failed to explode but Quyen took heart that, “because of Troi’s action, McNamara had to scurry like a rat” (17). Troi explained that “the Yankees are even more savage than the French, many times more so” (22). Colonized by the French until 1954, a Vietnamese description of their many years of French subjugation tells the story: “They have enforced inhuman laws. . . . They have built more prisons than schools. They have mercilessly slain our patriots, they have drowned uprisings in rivers of blood. They have fettered public opinion. . . . They have robbed us of our rice fields, our mines, our forests, and our raw materials” (Zinn, 460). Yet Troi regarded the U.S. occupiers as even worse: “I hate McNamara who has caused so much suffering. . . . That’s why I tried to kill him” (Van, 43). He concluded, “My one regret is that I failed to kill McNamara” (34).

Troi’s young widow Quyen said, “My husband was a liberation fighter in a secret commando unit operating in Saigon . . . he was given the task of killing McNamara by planting a bomb under the Cong Ly Bridge” (Van, 63). It failed to explode but Quyen took heart that, “because of Troi’s action, McNamara had to scurry like a rat” (17). Troi explained that “the Yankees are even more savage than the French, many times more so” (22). Colonized by the French until 1954, a Vietnamese description of their many years of French subjugation tells the story: “They have enforced inhuman laws. . . . They have built more prisons than schools. They have mercilessly slain our patriots, they have drowned uprisings in rivers of blood. They have fettered public opinion. . . . They have robbed us of our rice fields, our mines, our forests, and our raw materials” (Zinn, 460). Yet Troi regarded the U.S. occupiers as even worse: “I hate McNamara who has caused so much suffering. . . . That’s why I tried to kill him” (Van, 43). He concluded, “My one regret is that I failed to kill McNamara” (34).

The romance between Troi and Quyen was sweet but tragic. Troi had to keep his guerilla activities secret from his bride, and, after his arrest, he confessed to deceiving her but added, “I’m not ashamed, because I did it for the revolution” (48). He further revealed that he was authorized to go on leave but “insisted on carrying on” (56). He even sold his wedding ring for material and supplies for his liberation task at Cong Ly Bridge. She embraced his revolutionary zeal: “I want to live and fight like a Communist, although I’m not one yet” (61). He declared, “I always hoped that someday you would be my comrade as well as my wife” (56).

In one of Quyen’s visits to Troi in prison she too was arrested and imprisoned. She and Troi were celebrated by her fellow prisoners, saying to themselves and others when called to the torture chamber, “Let’s be as brave as Troi, let’s live like him” (Van, 45). Quyen’s prison comrades advised her to sing more than she cried and, if she must cry, do so in private and not before the enemy. They fought for spiritual nourishment, even for those awaiting execution, making the entire condemned block echo with revolutionary songs. And they wrote poetry celebrating “communist mettle” (20).

In October of 1964, in the first public execution of a Viet Cong cadre, Troi was handcuffed to a post where he was to be shot. Calm, dignified, and bearing “himself so firmly” (Van, 44), he defiantly cried out, “Long live people’s war! Death to U.S. imperialism!” and “Long Live Ho Chi Minh” (Powers, 196). In his final moments, as a priest offered him absolution, Troi exclaimed, “I have not sinned. It is the Americans who have sinned” (Van, 35). After the first volley he was hit in the chest but kept shouting “Long Live Vietnam!” (35). Some journalists present “could not help crying” (35).

Despite the watchful eyes of South Vietnam’s soldiers and police, mourners quickly made their way to Troi’s grave to celebrate him with “incense and flowers” (Van, 79). He was awarded the Bronze Citadel of the Fatherland medal (80) and is now celebrated in Vietnam and Cuba as a shining example for workers and students with “his portrait everywhere” (33). American activists Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden named their son Troy for him. Quyen swore that “the way you have lived, Troi, I promise to follow you to the end” (84).

Morrison “had to do something else . . . some dramatic gesture.”

Norman R. Morrison, a 31-year-old Quaker, father of three, and ardent pacifist from Baltimore, “was deeply moved by . . . the suffering of innocent Vietnamese women and children” (Steinbach, 10). A friend and fellow Quaker noted that Norman had been praying for god’s will for himself and, in response to the criminal war in Vietnam, “he’d been writing letters to editors, to congressmen, to the President, and the Pentagon; he’d participated in demonstrations and protests . . . to try to convince people that what we were doing in Vietnam was wrong . . . but it hadn’t worked. And now he had to do something else . . . some dramatic gesture” (6).

On November 2, 1965, he drove from his home to Washington, D.C., stopping en route to mail a letter to his wife: “Dearest Anne, for weeks, even months, I have been praying only that I be shown what I must do. This morning without warning I was shown. . . . Know that I love thee but must act” (Steinbach, 1). He took a gallon jug of kerosene along and his baby daughter Emily.

At the Pentagon, Morrison chose a spot “within full view of the office window of Secretary of Defense Robert Strange McNamara” (Zaroulis & Sullivan, 1). It was near dusk as thousands of Pentagon employees poured out of the building, headed for home. He doused himself, “struck the match on his shoe,” and created “a 7-foot-high pillar of flame” (Steinbach, 2). Witnesses said that he held the baby while he was on fire, while people yelled “Drop the baby!” (10). It seems unclear how, but Emily “emerged entirely unharmed” (King, 1), with one witness noting that “the baby on the ground, several feet away from him. He was staggering backwards. I couldn’t see if she had fallen or been placed down by him.” One of the first persons to reach Morrison said, “I saw his face. It was blank. He was still alive but there was no indication of pain. No indication of anything.” A physician at the scene said, “I knew he wasn’t going to make it. The fire was out but he was totally burned from top to bottom. . . . He died officially within two minutes” (Steinbach, 11).

Two days after Morrison’s death, his wife Anne received his farewell letter. Years later she said of his act, “A great weight came down upon us, creating a Before and After in our lives . . . we have suffered greatly, and still suffer to this day” (Steinbach, 5). She concluded, though, that “he must have weighed this against the suffering of the people of Vietnam. The loss of the Vietnamese is really so much greater than my loss” (9).

Many still wonder why Morrison took Emily with him that day, but Emily seems most certain of her father’s intentions: “I know that I was there intentionally . . . to be a symbol of the children who were suffering in Vietnam” (Steinbach, 2). Her sister Christina, then age 5, says, “I have often felt that, in a sense, my father sacrificed all five of us in hopes of saving the people of another country. As a child, I wondered if they were more important to him than we were” (7). And regarding her sister Emily’s presence at the immolation, she concludes that “he did sacrifice her in a sense by requiring her to witness his death and by leaving her there without him” (9).

“I was horrified, horrified by it,” Mr. McNamara said of Norman’s public self-immolation (Steinbach, 3). A month later, he wrote, “I didn’t think there was a chance of winning the war militarily. And I didn’t see any way out” (3). Before his death in 2009, he further admitted that he occasionally wept in public when mentioning Norman Morrison: “I get very emotional. I get very teary. I consider it a weakness” (15). Emily Morrison astutely “questions the depth of Robert McNamara’s mea culpa” (8).

Self-immolation is the ultimate form of protest, a primal scream. It emerged as a modern protest tactic on June 11, 1963, when Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức assumed the lotus position near a busy Saigon street and sacrificed himself in flames. He was protesting discrimination against Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government of Catholic and CIA puppet Ngo Dinh Diem. A photo of his horrific act won the World Press Photograph Award for 1963. Following his death, “four more monks and a nun set themselves ablaze protesting Diem before his regime collapsed in 1963” (Smith, 1). And Morrison became one of eight Americans who “burned themselves to death during the war” (King, 2).

Some are quick to dismiss such an act as crazy. But writer and LSD pioneer Aldus Huxley suggested that the truly mentally ill are those who quietly adapt to a sick society: “Their perfect adjustment to abnormal society is a measure of their mental sickness” (Perkins, 1).

A deeper look suggests that persons such as Morrison are committed, caring people who simply feel more. McNamara may have believed that feeling is weakness, but perhaps these individuals are more alive, so moved by injustice or the suffering of others that they willingly, even eagerly, sacrifice themselves to express their outrage. The act seems to be rooted in the Buddhist call to renounce the body and transcend its limitations. It is also a fierce desire to express sincerity of belief, exasperation from not being heard, and a desperate attempt to overcome frustration with normal avenues of protest. Guided by principles of nonviolence and motivated by feelings of love and concern for others, they seem to transcend ego and achieve selflessness. Then they alight themselves.

In 1965, 82-year-old Alice Herz self-immolated in Detroit after “returning from a demonstration against racial violence in Selma, Alabama” (Dvorak, 1). She had been “protesting the war in Vietnam and racial segregation in the American South” and “had told her friends and family she was not being heard” (2). The element of not being heard seems to be important in understanding those who act out in dramatic and public form.

As the slaughter of Vietnamese peasants dragged on, American protestors became more strident. The Weather Underground emerged from frustration with peaceful protest. They never deliberately killed themselves or anyone (Powers, 190) but ensured their own destruction through revolutionary strategies that were romantic at best and infantile at worst. For the Weathermen, “to suffer injury was proof of the authenticity of one’s commitment” (Isserman, 168). Young white radicals wanted to reject “white skin privilege” by facing the same risks as the Viet Cong and Black Panthers (168).

So, on a New York Friday morning, March 6, 1970, a lovely young woman “of uncommon character” named Diana Oughton went down into the basement of 18 West 11th Street (Powers, 183). A few minutes before noon an errant wire on a bomb caused an explosion that killed her and at least one fellow Weatherman. A police report read, “The people in the house were obviously putting together the component parts of a bomb and they did something wrong” (3). Police found “the tip of the little finger of someone’s right hand,” eventually identifying it as Oughton’s (4). The Weather Underground had lost faith in conventional political methods, and as one member said, “We combated liberalism in ourselves” (201). They wanted dramatic action toward revolution.

It seems clear that McNamara spent his final years trying to salvage his soul and make peace with “restless ghosts . . . who suffered and died in Vietnam (Steinbach, 3). Former New York Times editor Howell Raines reflected, “Surely he must in every quiet and prosperous moment hear the ceaseless whispers of those poor boys in the infantry, dying in the tall grass, platoon by platoon, for no purpose” so that “the ghosts of unlived lives circle close around Mr. McNamara” (Eschner, 1). Those unlived lives include 58,220 American dead, millions of Vietnamese dead, and Nguyen Van Troi and Norman R. Morrison.

Morrison’s family received a letter of condolence from the South Vietnam National Liberation Front on behalf of the Vietnamese people, calling Morrison’s self-immolation “sublime” (Steinbach, 14). A street in Hanoi was named for him and a commemorative stamp issued. Teachers in Nam Dinh City penned a poem in his honor:

A holy fire was set

Morrison! You heroic son

Made your body a living torch! (Steinbach, 14)

Sources

Judith Clavir Albert and Stewart Albert, The Sixties Papers (New York: Praeger, 1984).

Boston Lesbian Feminists, “Vietnam: A Feminist Analysis,” in The Radical Therapist (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1974).

Petula Dvorak, “Self-Immolation Can Be a Form of Protest,” Washington Post, May 30, 2019.

Kat Eschner, “How Robert McNamara Came to Regret the War He Escalated,” Smithsonian Magazine, Nov. 29, 2016.

Maurice Isserman, If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (New York: Basic Books, 1987).

Sallie B. King, “They Who Burned Themselves for Peace: Quaker and Buddhist Self-Immolators during the Vietnam War,” Buddhist-Christian Studies, January 2000.

Louis Menand, “Change Your Life: The Lessons of the New Left,” New Yorker, March 22, 2021, pp. 46–53.

Bob Perkins, “Self-Immolation: A Brief History of the Incomprehensible Act,” Community Corner, April 9, 2020. Patch.com.

Thomas Powers, Diana: The Making of a Terrorist (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1971).

Amanda Smith, “Self-Immolation: A History of the Ultimate Protest,” Rear Vision, ABC, June 1, 2016.

Alice Steinbach, “The Sacrifice of Norman Morrison,” Baltimore Sun, July 30, 1995.

Nick Turse, Kill Anything That Moves (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2013).

Tran Dinh Van, The Way He Lived: The Story of Nguyen Van Trỗi, as told by his widow, Thi Quyên Phan (South Vietnam: Liberation Publishing House, 1965).

Nancy Zaroulis and Gerald Sullivan, Who Spoke Up? American Protest against the War in Vietnam 1963–1975 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984).

David Zierler, The Invention of Ecocide (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Collins, 1980).

Images: Anti–Vietnam War protest, Wikipedia (public domain); Nguyễn Văn Trỗi, moments before execution (Wikipedia, fair use); Self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức (Wikipedia, public domain).

Join Now

Join Now